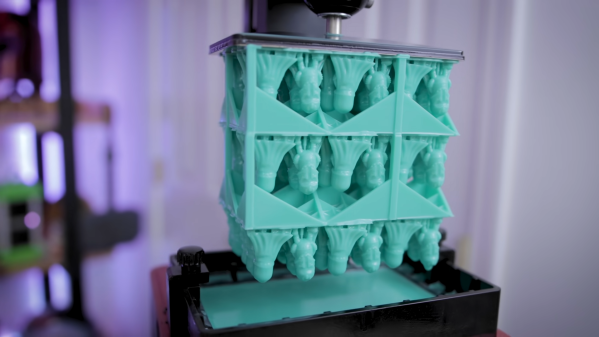

As anyone who has used a 3D printer before knows, what comes off the bed of your regular FSD printer is by no means a mirror finish. There are layers in the print simply by the nature of the technology itself, and the transitions between layers will never be smooth. In addition, printers can use different technology for depositing layers, making for thinner layers (SLA, for example). With those challenges in mind, [AlphaPhoenix] set out to create an authentic mirror finish on his 3D prints. (Video, embedded below.)

As the intro hints, mirrors need very flat/smooth surfaces to reflect light. To smooth his prints, [AlphaPhoenix] first did a light sanding pass and then applied very thick two-part epoxy, allowing surface tension to do the smoothing work for him. Once dried, silver was deposited onto the pieces via a few different sprays. First, a wetting agent is applied, which prevents subsequent solutions from beading up. Next, he sprays the two precursors, and they react together to deposit elemental silver onto the object’s surface. [AlphaPhoenix] asserts that he isn’t a chemist and then explains some of the many chemical reactions behind the process and theorizes why the solutions break down a while after being mixed.

He had an excellent first batch, and then subsequent batches came out splotchy and decided un-mirror-like. As we mentioned earlier, the first step was a wetting agent, which tended to react with the epoxy that He applied. Then, using a grid search with four variables, [AlphaPhoenix] trudged through the different configurations, landing on critical takeaways. For example, the curing time for the epoxy was essential and the ratio between the two precursor solutions.

Recently we covered a 3D printed mirror array that concealed a hidden message. Perhaps a future version of that could have the mirror integrated into the print itself using the techniques from [AlphaPhoenix]?