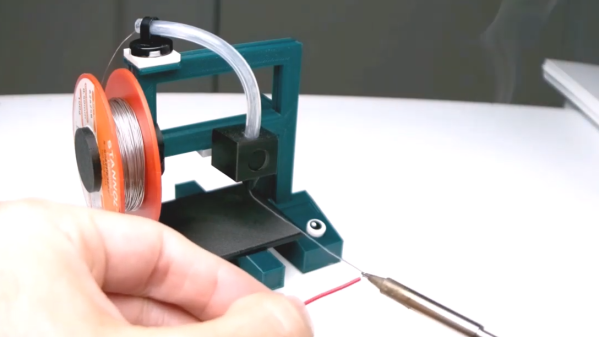

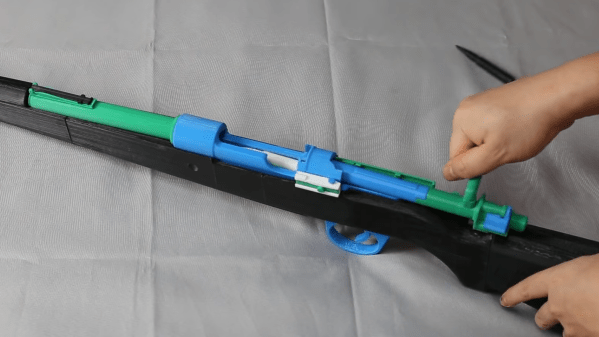

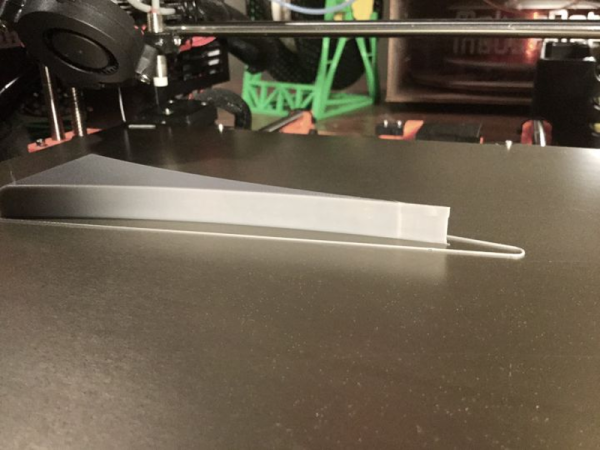

Most of us have bent a length of solder into a more convenient shape and angle when soldering, and just sort of pushed the soldering iron and work piece into the hanging solder instead of breaking out a third hand. Well, [yukseltemiz] seems to have decided that a solder dispenser and a miniature 3D printer model can have a lot in common, and created a 1/5 scale Ender 3 printer model that acts as a solder stand and dispenser. The solder spool hangs where the filament roll would go, and the solder itself is dispensed through the “print head”.

It’s cute, and we do like the way that [yukseltemiz] incorporated a few Lego pieces into the build. A swivel and eyelet guides the solder off the roll and a small Lego ball and socket gives the dispenser its articulation, an important feature for bending solder to a more convenient angle for working. It makes us think that using Lego pieces right alongside more traditional hardware like M3 nuts and bolts might be an under-explored technique. You can see the unit in action in the brief assembly video, embedded below.

Continue reading “Whimsical Solder Stand Moonlights As Toy 3D Printer”