YouTuber and electronics engineer [Carl Bugeja] has a knack for finding creative uses for flexible PCBs. For the past year, he has been experimenting with PCB motors, using them on drones, robot fish, and most recently swarm robots. This is his final video in the vibro-bot series, and he’s got his best results to date. (Embedded below.)

He started off with flexible PCB actuators as robotic legs and magnets fitted into 3D-printed shells. The flexible PCB actuators work as inefficient electromagnets, efficient enough to react to a magnet when a current runs through, but not so efficient that they don’t release immediately.

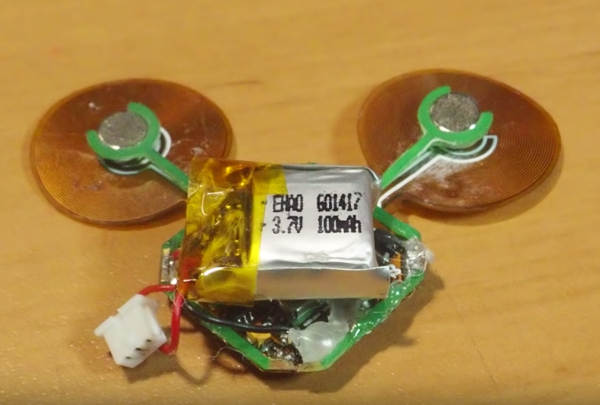

The most recent design uses a rigid 0.6 mm FR4 PCB that acts as the frame to prevent the middle of the robot from bending. The “brain” of the robot is located at its center, which is connected to the flexible PCB actuators. Since the biggest constraint on his past robots was weight, he removed two of the legs to reduce the weight by 20%, resulting in straighter walks. He also added a Bluetooth module to wirelessly control the robot and replaced his old LiPo with a new, lighter battery (28 mAh, 15 C, 420 mA).

His latest video now shows that the robot is able to move forwards, backwards, and side to side. That’s a huge improvement over his previous attempts, which mostly resulted in the robot vibrating in place or flopping around his workbench. It’s not going to fetch you a beer, but it’s really cool.

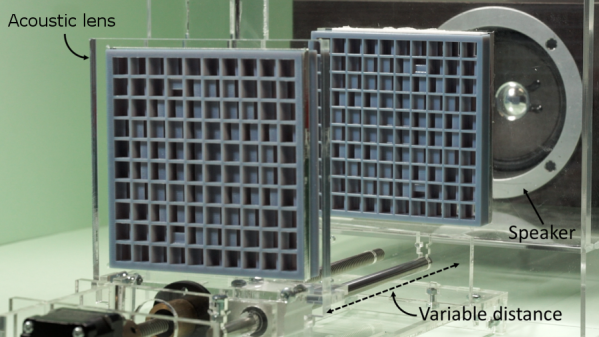

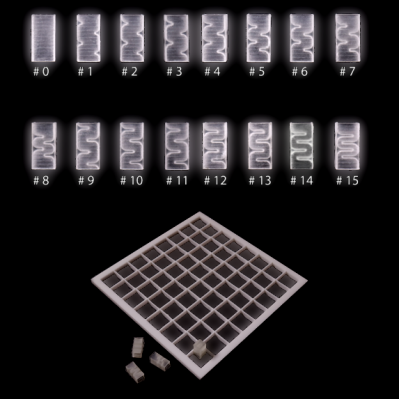

Researchers from the University of Sussex used 3D printing for a modular approach to acoustic lens design. 16 different pre-printed “bricks” (shown here) can be assembled in various combinations to get different results. There are limitations, however. The demonstration lenses only work in a narrow bandwidth, meaning that the sound they work with is limited to about an octave at best. That’s enough for a simple melody, but not nearly enough to cover a human’s full audible range.

Researchers from the University of Sussex used 3D printing for a modular approach to acoustic lens design. 16 different pre-printed “bricks” (shown here) can be assembled in various combinations to get different results. There are limitations, however. The demonstration lenses only work in a narrow bandwidth, meaning that the sound they work with is limited to about an octave at best. That’s enough for a simple melody, but not nearly enough to cover a human’s full audible range.

The payload container is a hollow tube with a 3D printed threaded adaptor attached to one end. Payload goes into the tube, and the tube inserts into a hole in the bulkhead, screwing down securely. The result is an easy way to send up something like a GPS tracker, possibly with a LoRa module attached to it. That combination is a popular one with high-altitude balloons, which, like rockets, also require people to retrieve them after not-entirely-predictable landings. LoRa wireless communications have very long range, but that doesn’t help if there’s an obstruction like a hill between you and the transmitter. In those cases,

The payload container is a hollow tube with a 3D printed threaded adaptor attached to one end. Payload goes into the tube, and the tube inserts into a hole in the bulkhead, screwing down securely. The result is an easy way to send up something like a GPS tracker, possibly with a LoRa module attached to it. That combination is a popular one with high-altitude balloons, which, like rockets, also require people to retrieve them after not-entirely-predictable landings. LoRa wireless communications have very long range, but that doesn’t help if there’s an obstruction like a hill between you and the transmitter. In those cases,