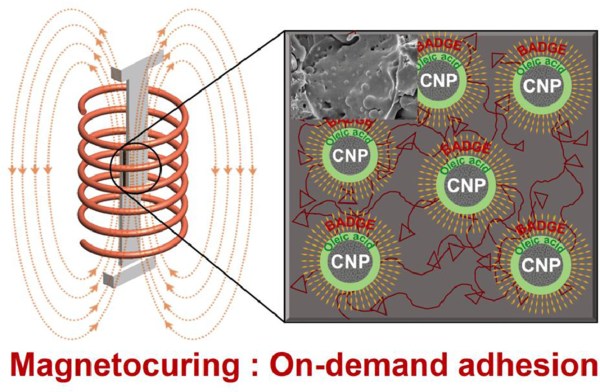

Who doesn’t love epoxy? Epoxy resins, also known as polyepoxides, are an essential adhesive in many applications, both industrially and at smaller scales. Many polyepoxides however require the application of heat (around 150 °C for most types) in order to cure (harden), which can be complicated when the resin is applied to or inside layers of temperature sensitive materials. Now researchers at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore have found a way to heat up resins using an alternating magnetic field (PDF), so-called magnetocuring.

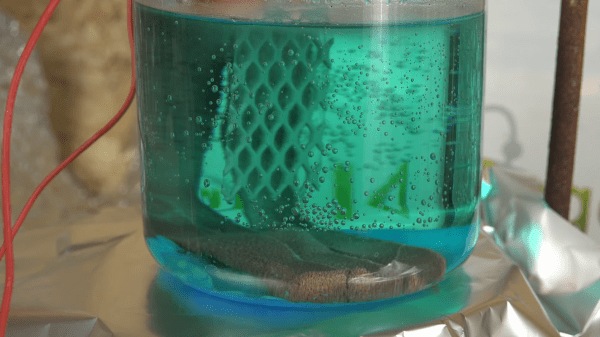

As detailed in the research article by R. Chaudhary et al., they used commercially available epoxy resin and added nano particles of a MnxZn1-xFe2O4 alloy. This mixture was exposed to an alternating magnetic field to induce currents in the nano particles and subsequently produce heat that served to raise the temperature of the surrounding resin to about 160 °C in five minutes, allowing the resin to cure. There is no risk of overheating, as the nano particles are engineered to reach their Curie temperature, at which point the magnetic field no longer affects them. The exact Curie temperature was tweaked by changing the amount of manganese and zinc in the alloy.

After trying out a number of different alloy formulations, they settled on Mn0.7Zn0.3Fe2O4 as the optimal formulation at which no resin scorching occurred. As with all research it’s hard to tell when (and if) it will make it into commercial applications, but if this type of technology works out we could soon be gluing parts together using epoxy resin and an EM field instead of fumbling with the joys of two-component epoxy.

(Thanks, Qes)