Is it a hack? We think it’s definitely a hack. It’s just a hack that’s so grand and audacious it’s hard to even think of it as a hack. [Don Justo Martinez] single-handedly (aside from the help of an occasional nephew, which doesn’t count) built a Cathedral over 53 years in Madrid Spain.

Born in 1925, [Don Justo] found himself dying of tuberculosis soon after leaving a life of farming and becoming a Benedictine monk. He became so ill he was forced to leave his order and prayed for healing. He promised that he would erect a church in the name of the Lady of the Pillar if he lived.

He lived, and he built. He built out of whatever he could find. The broken bricks from the local factory became his cut stone. Discarded glass and metal all went into the work. The column forms are old oil drums. As Linus Torvalds said of the Linux project, (paraphrase) “Start to build it and they will come.” Once people saw the madman work, they began to donate materials to the Cathedral.

An untold number of very difficult man hours has gone into the structure. It makes the complaining in the comments about the 100 hours spent on St. Optimus of Prime look as petty as it was. It makes most arguments about time spent look silly. It’s labor and dedication on a scale that just isn’t often seen in any age.

In the tradition of cathedrals, [Don Justo] is likely to pass away before his church is finished. His only request is that he be the first to be placed in its crypts. His great hope is that others will continue the work after him. If you’d like to know more and see some pictures there is a website with more information.

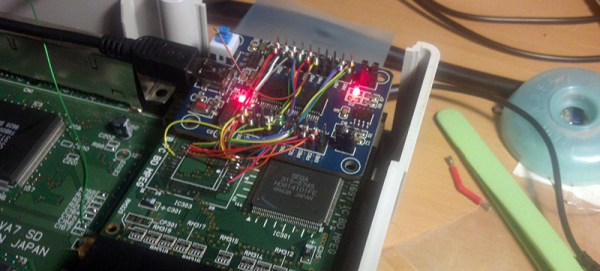

According to [jhl], the design of the Sega Saturn is tremendously complicated. There’s an entire chip dedicated to controlling the CD drive, and after some serious reverse engineering work, [jhl] had it pretty much figured out. The question then was how to load data onto the Saturn. For that. [jhl]

According to [jhl], the design of the Sega Saturn is tremendously complicated. There’s an entire chip dedicated to controlling the CD drive, and after some serious reverse engineering work, [jhl] had it pretty much figured out. The question then was how to load data onto the Saturn. For that. [jhl]