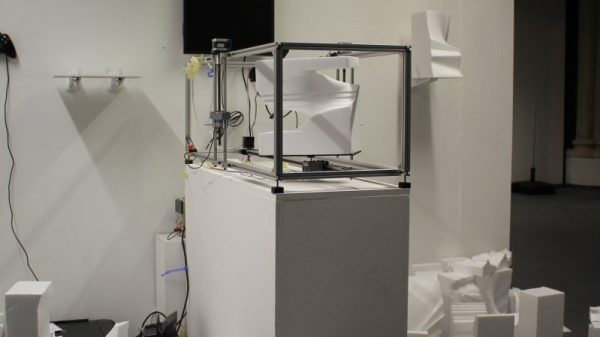

Macro photography is the art of taking photos of things very close up, and ideally at great detail. Unfortunately cameras have poor depth of field at close ranges, so to get around this, many use focus stacking techniques. This involves taking many photos at different focal lengths and digitally compositing them together. To help achieve this, [gtoal] realized that garden variety CNC machines would be perfect for the job.

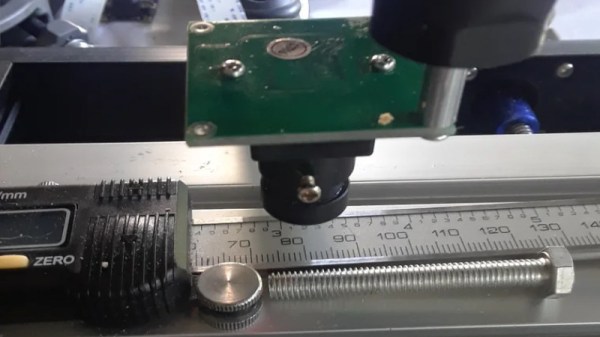

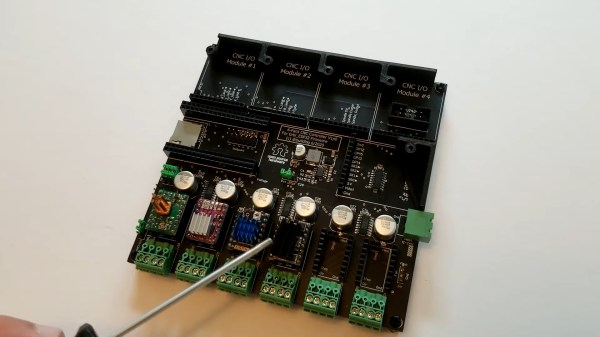

To focus stack effectively, it’s desirable to move the camera in very small increments of sub-mm precision, in order to get different parts of the subject in focus. For this, a CNC machine excels, as it’s designed to move tool heads in very tiny, precise movements.

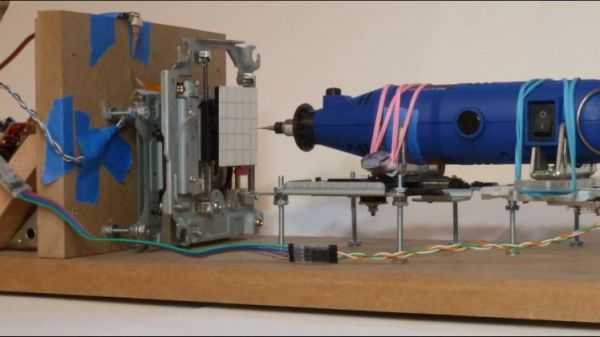

To achieve a bargain focus stacking rig, [gtoal] used a Dremel tool mount for cutting discs. It’s repurposed here, used as an easy way to fit a Raspberry Pi camera to a CNC tool head through its mounting holes. From there, it’s a simple manner of stepping the CNC a tiny amount at a time on the Z-axis, while taking photos with the Raspberry Pi along the way. [gtoal] notes that it would be simple for an experienced CNC user to whip up a program to automate the entire process.

We’ve seen other budget focus stacking rigs before, and even a busted 3D printer that was turned into an automated scanning microscope. If you’ve got your own tricks for top notch macro photography, drop us a note in the tipline!