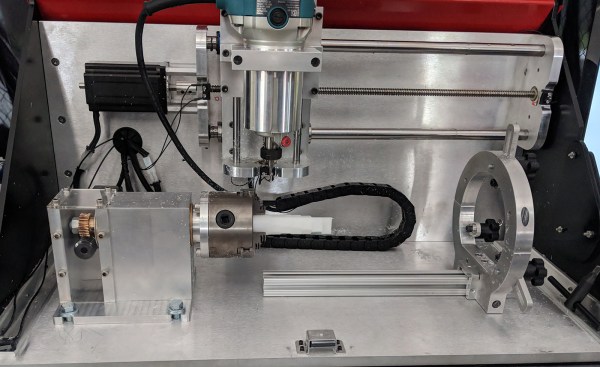

There’s a certain class of parts that just can’t be made on a standard 3-axis mill, nor with a 3D printer or a lathe. These parts — weird screws, camshafts, strange gears, or simply a shaft with a keyway (or two) — can really only be made with a rotary axis on a CNC machine. Sure, you could buy a rotary axis for a Haas or Tormach for thousands of dollars, or you could build your own. That’s exactly what [Adam Zeloof] and [Matt Martone] did with their project at this year’s World Maker Faire in New York. It’s the Rotomill, a simple three-axis CNC machine, with a rotary axis, that just about anyone can build.

The design of the Rotomill uses a standard, off-the-shelf Makita rotary tool for the spindle, and uses leadscrews to move the X and Z axes around with NEMA 24 stepper motors. The A axis — the rotary bit — is driven through a worm gear, also powered by a NEMA 24. Right now this provides more than enough power to cut foam, plastic, and wood, and should be enough to cut aluminum. That last feat is as yet untested, but the design is open enough that a much more powerful spindle could be attached.

The software for this machine is a bit weird. For most CNC machines with a rotary axis, the A axis is treated as such — a rotary axis. For the Rotomill, [Adam] and [Matt] are generating G Code like it’s a normal Cartesian machine, only with one axis ‘wrapped’ around itself. This is all done through Autodesk HSM, and a properly configured Arduino running GRBL makes sense of all this arcane geometry.

It’s a great looking machine, and the guys behind it say it’s significantly less expensive than any other machine with a rotary axis. That’s to be expected, as it’s basically a five axis mill with two axes removed. Still, this entire project was built for about $2000, and some enterprising salvage and hacking could bring that price down a bit.

The full MatchSticks creation flow goes like this:

The full MatchSticks creation flow goes like this: