Software developers won’t ever run out of subjects to argue and fight about. Some of them can be fundamental to a project — like choice of language or the programming paradigm to begin with. Others seem more of a personal preference at first, but can end up equally fundamental on a bigger scale — like which character to choose for indentation, where to place the curly braces, or how to handle line breaks. Latest when there’s more than one developer collaborating, it’s time to find a common agreement in form of a coding style guide, which might of course require a bit of compromise.

Regardless of taste, the worst decision is having no decision, and even if you don’t agree with a specific detail, it’s usually best to make peace with it for the benefit of uniformly formatted code. In a professional environment, a style guide was ideally worked out collaboratively inside or between teams, and input and opinions of everyone involved were taken into consideration — and if your company doesn’t have one to begin with, the best step to take is probably one towards the exit.

The situation can get a bit more complex in open source projects though, depending on the structure and size of a project. If no official style guide exists, the graceful thing to do is to simply adopt the code base’s current style when contributing to it. But larger projects that are accustomed to a multitude of random contributors will typically have one defined, which was either worked out by the core developers, or declared by its benevolent dictator for life.

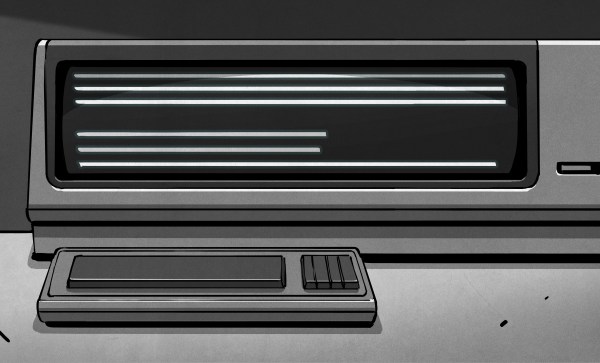

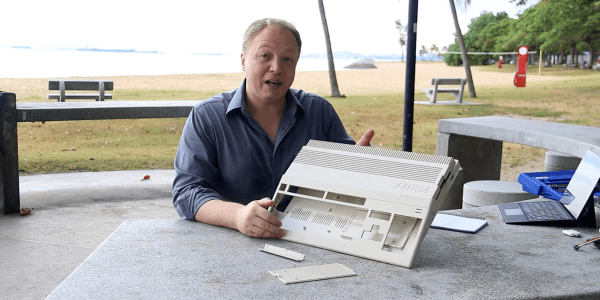

In case of the Linux kernel, that’s of course [Linus Torvalds], who has recently shaken up the community with a mailing list response declaring an overly common, often even unwritten rule of code formatting as essentially obsolete: the 80-character line limitation. Considering the notoriety of his rants and crudeness, his response, which was initiated by a line break change in the submitted patch, seems downright diplomatic this time.

[Linus]’ reasoning against a continuing enforcement of 80-char line limits is primarly the fact that screens are simply big enough today to comfortably fit longer lines, even with multiple terminals (or windows) next to each other. As he puts it, the only reason to stick to the limitation is using an actual VT100, which won’t serve much use in kernel development anyway.

Allowing longer lines on the other hand would encourage the use of more verbose variable names and whitespace, which in turn would actually increase readability. Of course, all to a certain extent, and [Linus] obviously doesn’t call for abolishing line breaks altogether. But he has a point; does it really make sense to stick to a decades old, nowadays rather arbitrary-seeming limitation in 2020?

Continue reading “Ask Hackaday: Are 80 Characters Per Line Still Reasonable In 2020?” →

Though the news coincides with increased traffic to the ISS, this move stems from a more serious issue with bacterial contamination during longer-term space travel. Today’s ISS toilets already recycle urine back into potable water and scrub the air reclaimed from solid waste as it gets compacted and stored. The new UWMS will act more like a food dehydrator, reducing the water content as much as possible to save on space, and petrifying the poo to inactivate the bacteria.

Though the news coincides with increased traffic to the ISS, this move stems from a more serious issue with bacterial contamination during longer-term space travel. Today’s ISS toilets already recycle urine back into potable water and scrub the air reclaimed from solid waste as it gets compacted and stored. The new UWMS will act more like a food dehydrator, reducing the water content as much as possible to save on space, and petrifying the poo to inactivate the bacteria.