Last week, I covered some of the bitter details of an interesting hack that lets us split up the I²C clock line into multiple outputs with a demultiplexer, effectively giving us “Chip Selects” for devices with the same address.

This week, I figured it’d be best to layout a slightly more practical method for solving the same problem of talking to I²C devices that each have the same address.

I actually had a great collection of comments mention the same family of chips I’m using to tackle this issue, and I’m glad that we’re jumping off the same lead as we explore the design space.

Recalling the Work of Our Predecessors

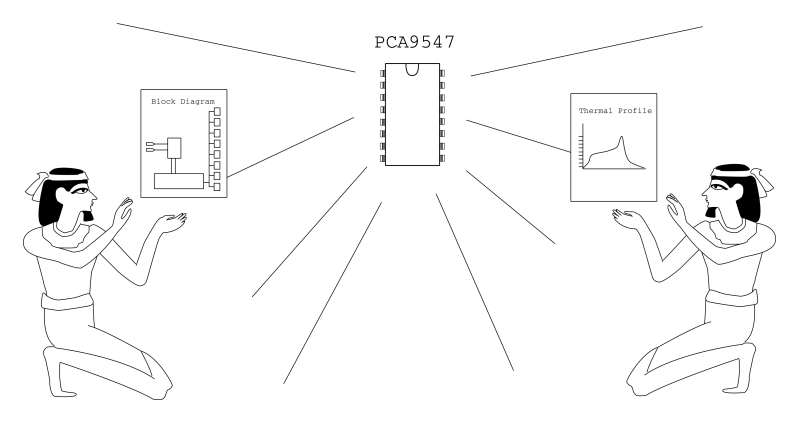

Before figuring out a clever way of hacking together our own solution, it’s best to see if someone before us has already gone through all of the trouble to solve that problem. In this case–we’re in luck–so much that the exact bus-splitting behavior we want is embedded into a discrete IC, known as the PCA9547.

It’s worth remembering that our predecessors have labored tirelessly to create such a commodity piece of silicon.

The PCA9547 (PDF) is an octal, I²C bus multiplexer, and I daresay, it’s probably the most practical solution for this scenario. Not only does the chip provide 8 separate buses, up to seven more additional PCA9547s can be connected to enable communication with up to 64 identical devices! What’s more, the PCA9547 comes with the additional benefit of being compatible with both 3.3V and 5V logic-level devices on separate buses. Finally, as opposed to last week’s “hack,” each bus is bidirectional, which means the PCA9547 is fully compliant with the I²C spec.

Selecting one of the eight I²C buses is done via a transfer on the I²C bus itself. It’s worth mentioning that this method does introduce a small amount of latency compared to the previous clock-splitter solution from last week. Nevertheless, if you’re planning to read multiple devices sequentially from a single bus anyway, then getting as close-as-possible to a simultaneous read/write from each device isn’t likely a constraint on your system.

With a breakout board to expose the pads, I mocked up a quick-n-dirty Arduino Library to get the conversation started and duplicated last week’s demo.

Happily enough, with a single function to change the bus address, the PCA9547 is pretty much a drop-in solution that “just works.” It’s definitely reassuring that we can stand on the shoulders of our chip designers to get the job done quickly. (They’ve also likely done quite a bit more testing to ensure their device performs as promised.) Just like last week, feel free to check out the demo source code up on Github.

Until next time–cheers!