From the early days of ARPANET until the dawn of the World Wide Web (WWW), the internet was primarily the domain of researchers, teachers and students, with hobbyists running their own BBS servers you could dial into, yet not connected to the internet. Pitched in 1989 by Tim Berners-Lee while working at CERN, the WWW was intended as an information management system that’d provide standardized access to information using HTTP as the transfer protocol and HTML and later CSS to create formatted documents inspired by the SGML standard. Even better, it allowed for WWW forums and personal websites to begin to pop up, enabling the eternal joy of web rings, animated GIFs and forums on any conceivable topic.

During the early 90s, as the newly opened WWW began to gain traction with the public, the Mosaic browser formed the backbone of the WWW browsers (‘web browsers’) of the time, including Internet Explorer – which licensed the Mosaic code – and the Mosaic-based Netscape Navigator. With the WWW standards set by the – Berners-Lee-founded – World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the stage appeared to be set for an open and fair playing field for all. What we got instead was the brawl referred to as the ‘browser wars‘, which – although changed – continues to this day.

Today it isn’t Microsoft’s Internet Explorer that’s ruling the WWW while setting the course for new web standards, but instead we have Google’s Chrome browser partying like it’s the early 2000s and it’s wearing an IE mask. With former competitors like Opera and Microsoft having switched to the Chromium browser engine that underlies Chrome, what does this tell us about the chances for alternative browsers and the future of the WWW?

Continue reading “The Modern WWW, Or: Where Do We Want To Go From Here?”

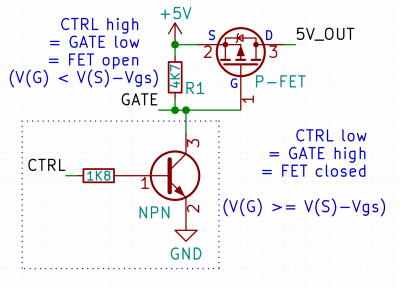

Here’s a simple FET circuit that lets you switch power to, say, a USB port, kind of like a valve that interrupts the current flow. This circuit uses a P-FET – to turn the power on, open the FET by bringing the GATE signal down to ground level, and to switch it off, close the FET by bringing the GATE back up, where the resistor holds it by default. If you want to control it from a 3.3 V MCU that can’t handle the high-side voltage on its pins, you can add a NPN transistor section as shown – this inverts the logic, making it into a more intuitive “high=on, low=off”, and, you no longer risk a GPIO!

Here’s a simple FET circuit that lets you switch power to, say, a USB port, kind of like a valve that interrupts the current flow. This circuit uses a P-FET – to turn the power on, open the FET by bringing the GATE signal down to ground level, and to switch it off, close the FET by bringing the GATE back up, where the resistor holds it by default. If you want to control it from a 3.3 V MCU that can’t handle the high-side voltage on its pins, you can add a NPN transistor section as shown – this inverts the logic, making it into a more intuitive “high=on, low=off”, and, you no longer risk a GPIO!