When we run an article with “DOOM” in the title, it’s typically another example of getting the venerable game running on some minimalist platform. This DOOM-based VR rig for rats, though, is less about hacking DOOM, and more about hacking the rats.

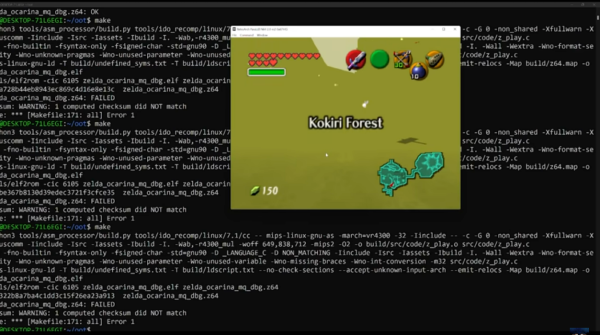

What started as a side project for [Viktor Tóth] has evolved into quite a complex apparatus. At the center of the rig is an omnidirectional treadmill comprised of a polystyrene ball about the size of a bowling ball. The ball is free to rotate, with sensors detecting rotation in two axes — it’s basically a big electromechanical mouse upside down. The rat rides at the top of the ball, wearing a harness to keep it from slipping off. A large curved monitor sits right in front of the rat to display the virtual environment, which is a custom DOOM map.

With the VR rig built, [Viktor] worked on automating the training. A treat dispenser provides the proper motivation, while powered drive wheels engage with the ball to nudge the rat if it gets stuck in the virtual world. [Viktor] says he has trained three rats — [Romero], [Carmack], and [Tom] — to walk down a straight hallway using this automated method. As for the meat of the game — shooting monsters — [Viktor] has that covered too, with a sensor that detects when a rat rears up on its hind legs to register a shot.

Total training time to get the rats to the point seen in the video was about six weeks, and [Viktor] reports the whole thing cost him about $2000. That’s a lot of time and money, but the results are pretty interesting. If you’re more interested in minimalist DOOM builds, we understand — check out DOOM on a lightbulb, or a thermostat, or even a GPS.

Continue reading “Rats Learn To Play DOOM In This Automated VR Arena”