Remember the pistol controller for the original Atari 2600? No? Perhaps that’s because it never existed. But now that we’re living in the future, adding a pistol to the classic games of the 2600 is actually possible.

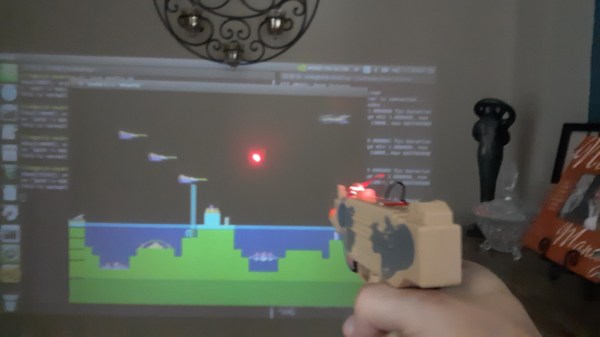

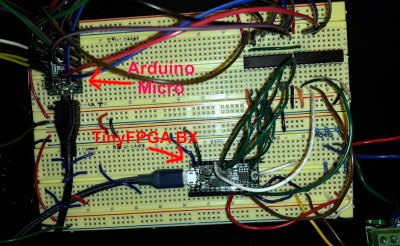

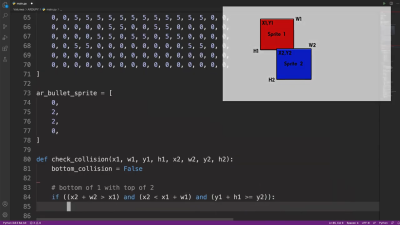

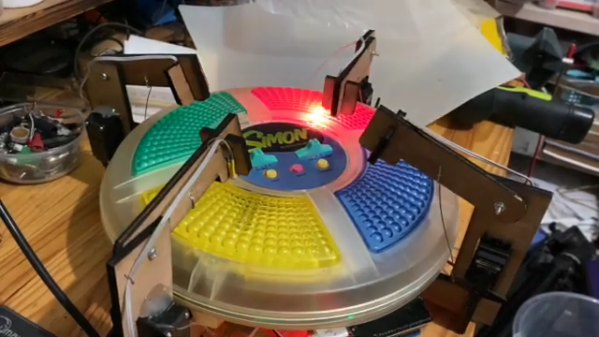

Possible, but not exactly easy. [Nick Bild]’s approach to the problem is based on machine vision, using an NVIDIA Xavier NX to run an Atari 2600 emulator. The game is projected on a wall, while a camera watches the game field. A toy pistol with a laser pointer attached to it blasts away at targets, while OpenCV is used to find the spots that have been hit by the laser. A Python program matches up the coordinates of the laser blasts with coordinates within the game, and then fires off a sequence of keyboard commands to fire the blasters in the game. Basically, the game plays itself based on where it sees the laser shots. You can check out the system in the video below.

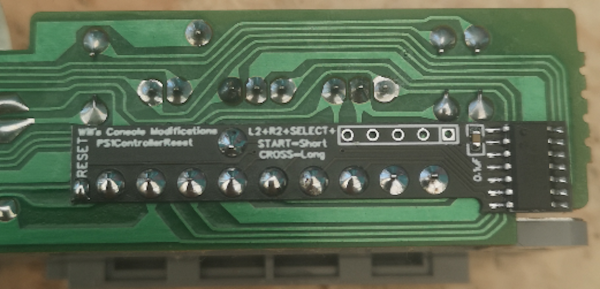

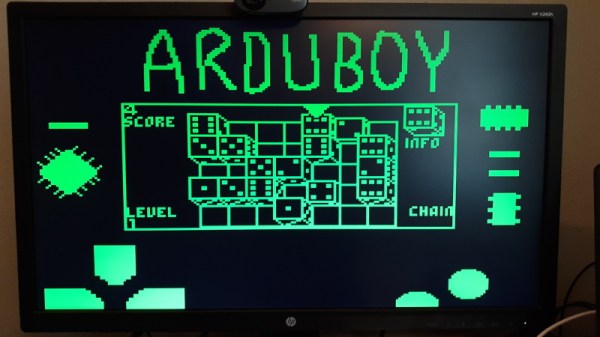

[Nick Bild] had a busy weekend of hacking. This was the third project write-up he sent us, after his big-screen Arduboy build and his C64 smartwatch.

Continue reading “Adding A Laser Blaster To Classic Atari 2600 Games With Machine Vision”