[bhunting] lives right up against the Rockies, and for a while he’s wanted to measure the temperature variations against the inside of his house against the temperature swings outside. The sensible way to do this would be to put a few wireless temperature-logging probes around the house, and log all that data with a computer. A temperature sensor, microcontroller, wireless module, battery, case, and miscellaneous parts meant each node in the sensor grid would cost about $10. The other day, [bhunting] came across the exact same thing in the clearance bin of Walmart – $10 for a wireless temperature sensor, and the only thing he would have to do is reverse engineer the protocol.

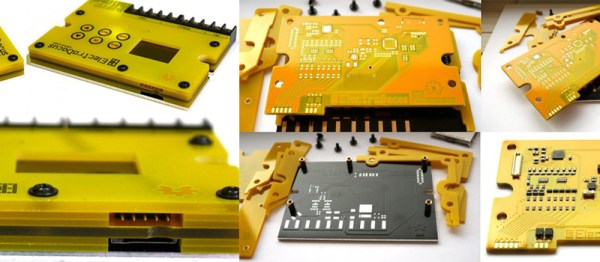

These wireless temperature sensors are exactly what you would expect for a cheap piece of Chinese electronics found in the clearance bin at Walmart. There’s a small radio operating at 433MHz, a temperature sensor, and a microcontroller under a blob of epoxy. The microcontroller and transmitter board in the temperature sensor were only attached by a ribbon cable, and each of the lines were labeled. After finding power and ground, [bhunting] took a scope to the wires that provided the data to the radio and took a look at it with a logic analyzer.

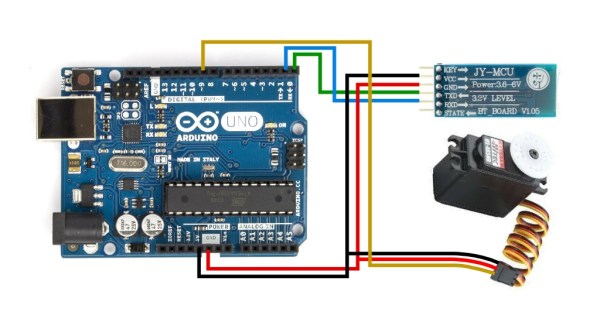

After a bit of work, [bhunting] was able to figure out how the temperature sensor sent data back to the base station, and with a bit of surgery to one of these base stations, he had a way to read the temperature data with an Arduino. From there, it’s just a data logging problem that’s easily solved with Excel, and [bhunting] has exactly what he originally wanted, thanks to a find in the Walmart clearance bin.