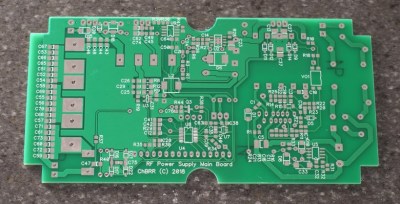

For his Hackaday Prize entry, [Martin] is building an Open Source Multimeter that can measure voltage, current, and power. It’s an amazing build, and you too can build one yourself.

The features for this multimeter consist of voltage mode with a range of +/-6V and +/-60V. There’s a current mode, basically the same as voltage, with a range of +/-60 mA and +/-500mA. Unlike our bright yellow Fluke, there’s also a power mode that measures voltage and current at the same time, with all four combinations of ranges available. There’s a continuity test that sounds a buzzer when the resistance is below 50 Ω, and a component test mode that measures resistors, caps, and diodes. There’s a fully isolated USB interface capable of receiving commands and transmitting data, a real-time clock, and in the future there might be frequency measurement.

This build is based on the STM32F103 microcontroller, uses an old Nokia phone screen, and unlike so many other multimeters, this thing is small. It’s very small. More than small enough to fit in your pocket and forget about it, unlike nearly every other multimeter available. There’s one thing about multimeters, and it’s that the best multimeter is the one that you have in your hands when you need it, and this one certainly fits the bill.

The entire project is being written up on hackaday.io, there’s a GitHub repo for all the hardware and software, and there’s also a video demo covering all the features (available below). This is a stand-out project, and something we desperately want to get our hands on.

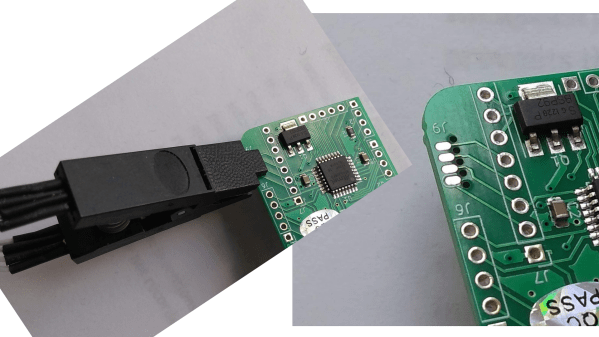

your magic smoke. Even if you are lucky, stray parts are the root of boundless malfunctions from disruptive to deadly. [TheRainHarvester] shares his trick for

your magic smoke. Even if you are lucky, stray parts are the root of boundless malfunctions from disruptive to deadly. [TheRainHarvester] shares his trick for

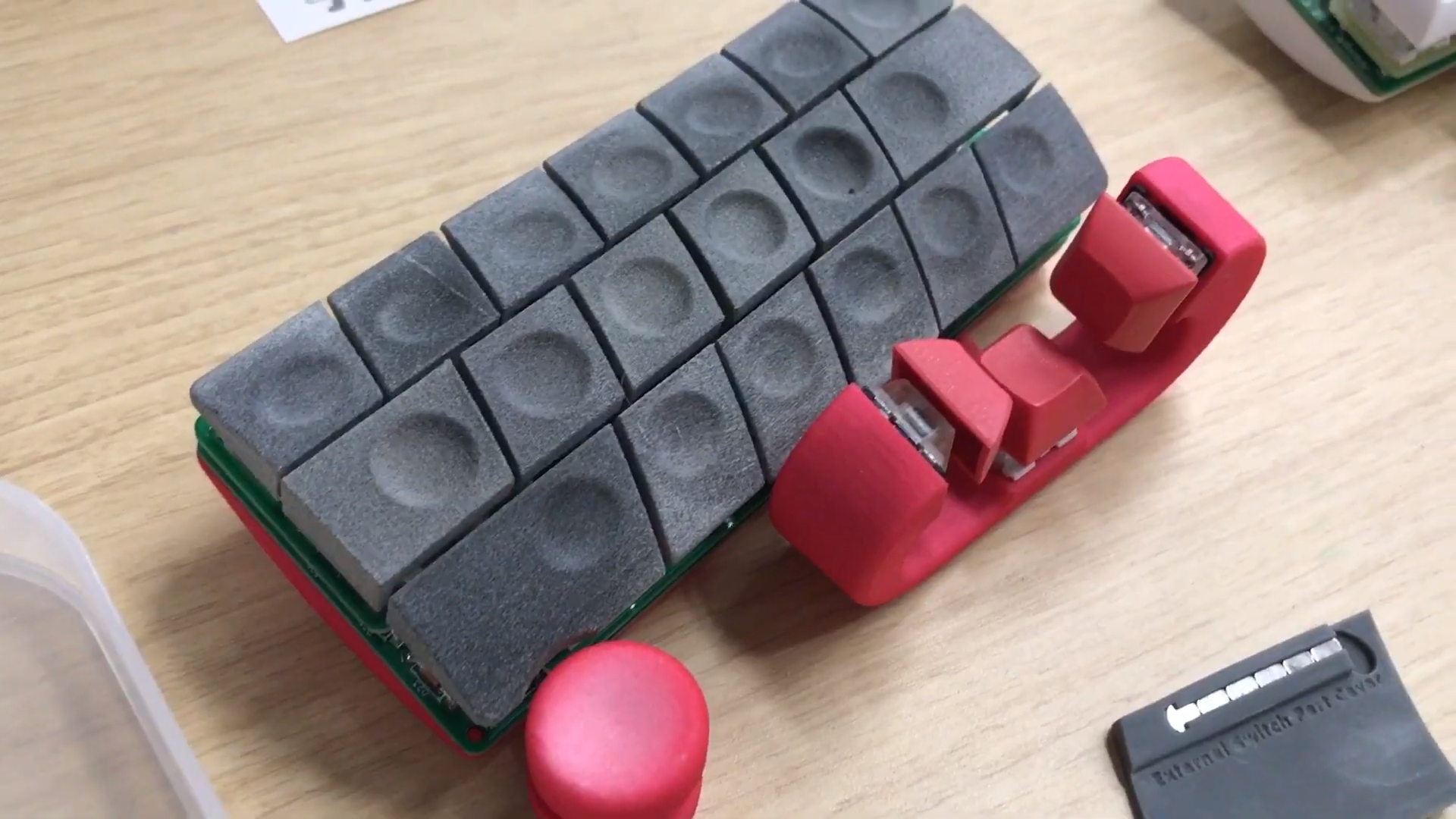

Speaking of [romly], one of their designs stands out as particularly unusual. There are a few things to note here. One is the very conspicuous

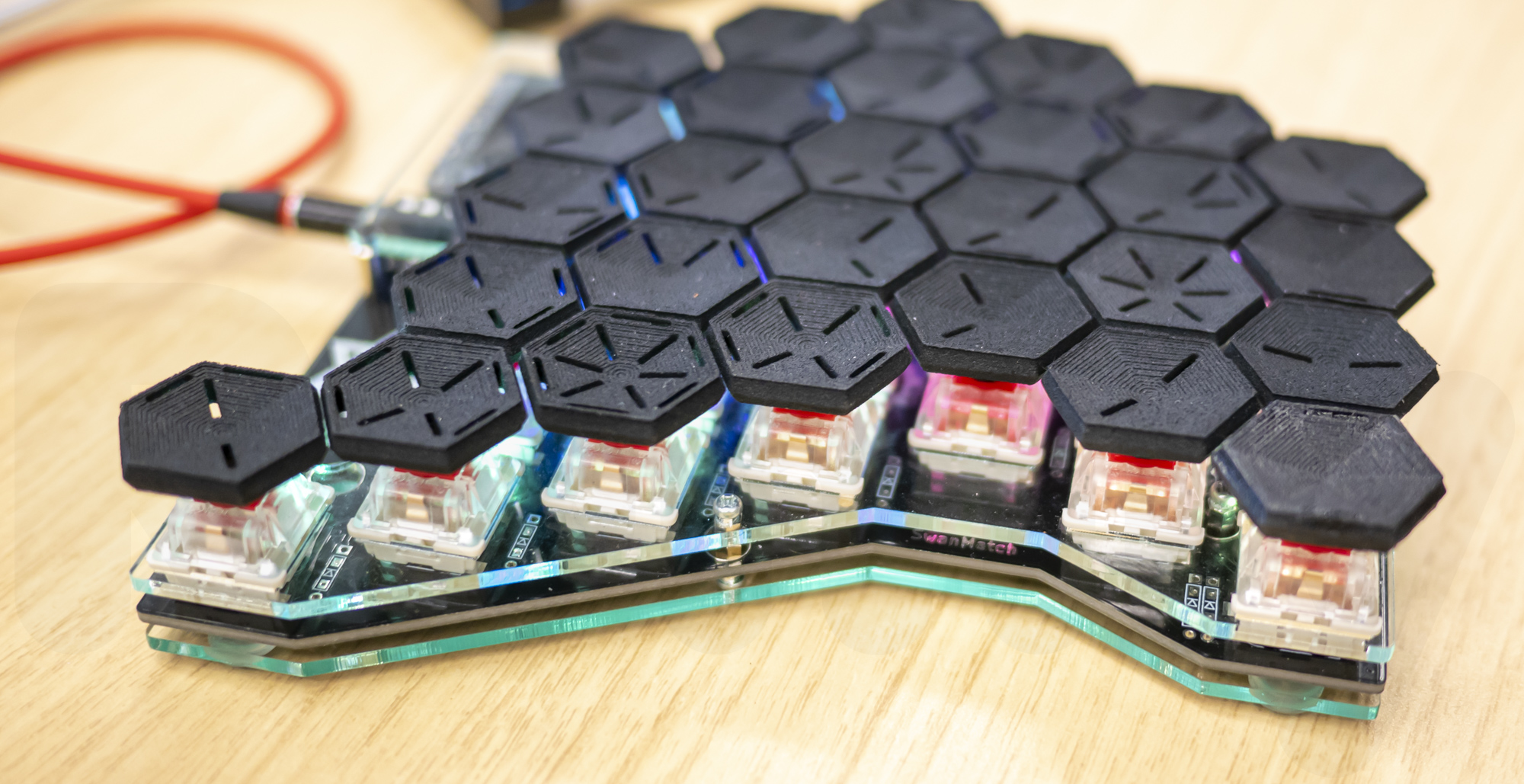

Speaking of [romly], one of their designs stands out as particularly unusual. There are a few things to note here. One is the very conspicuous  Another interesting entrant is this keyboard with unusually staggered switches and hexagonal caps (check out the individual markings!). Very broadly there are two typical keyboard layout styles; the diagonal columns of QWERTY (derived from a typewriter in the 1800’s) or the non slanted columns of an “

Another interesting entrant is this keyboard with unusually staggered switches and hexagonal caps (check out the individual markings!). Very broadly there are two typical keyboard layout styles; the diagonal columns of QWERTY (derived from a typewriter in the 1800’s) or the non slanted columns of an “