[Maarten Tromp] recently took the time to document some of the unusual and creative electronic projects he received as gifts over the years. These gadgets were created in the early 2000’s and still work flawlessly today. Two of our favorites are shown here: Hardware Tetris Unit (shown in the image above) and Heap of Electronic Parts.

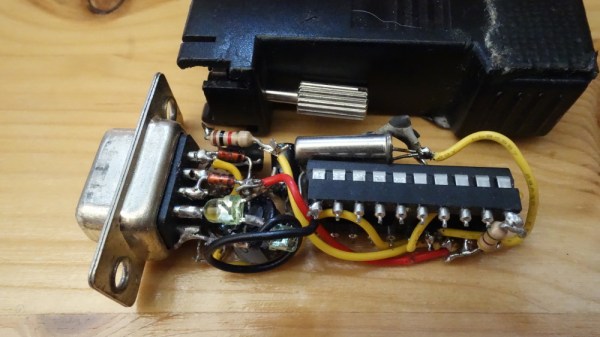

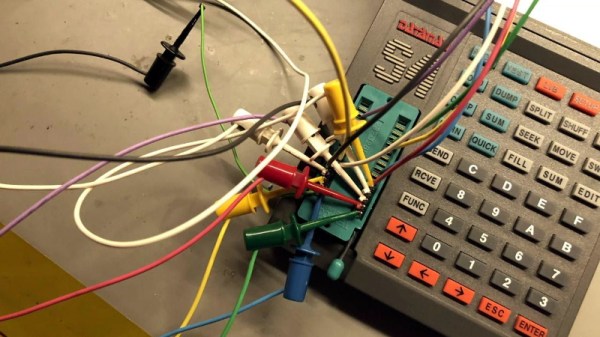

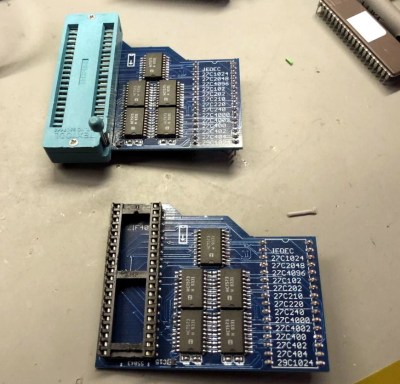

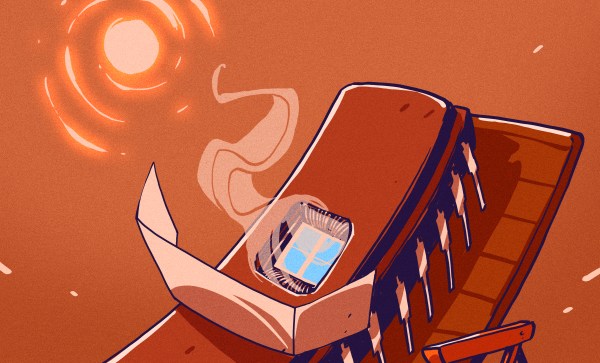

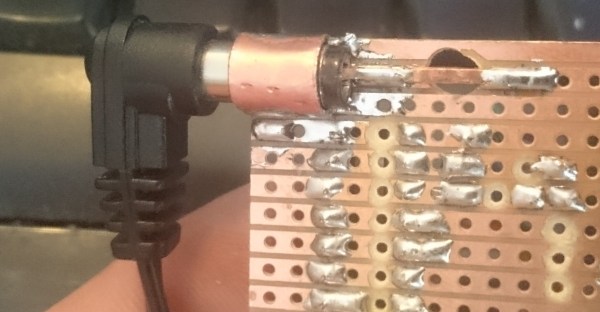

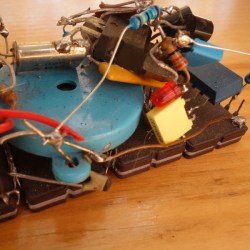

Heap of Electronic Parts was a kind of hardware puzzle and certainly lives up to its name. It’s a bunch of parts soldered in a mystifying way to the backs of four old EPROMs — the chips with the little window through which UV is used to erase the contents. Assured that the unit really did have a function, [Maarten] eventually figured out that when placed in sunlight, the device ticks, buzzes, and squeals. [Jeroen] had figured out that the EPROMs could act like tiny solar cells when placed in sunlight, and together the four generate just enough power to drive an oscillator connected to a piezo speaker. It still chirps happily away, even today.

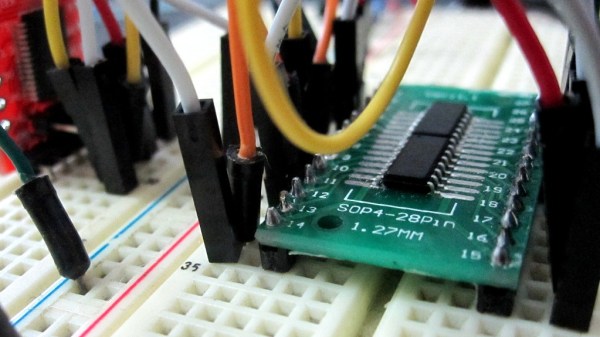

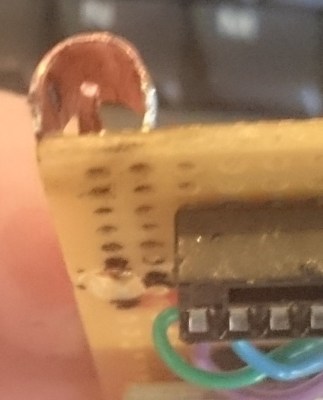

Hardware Tetris Unit was a black box intended to be plugged into a serial port. With a terminal opened using the correct serial port settings, a fully-functional Tetris game using ASCII-art graphics could be played. It was even self-powered from the serial port pins.

Inside Hardware Tetris is an AVR microcontroller with some level shifters, and the source code and schematics are available for download. 14 years later, computers no longer have hardware serial ports but [Maarten] says a USB-to-serial converter worked just fine and the device still functions perfectly.

There are a couple more devices documented on [Maarten]’s gifts page, including a Zork-inspired mini text adventure and a hardware board that does some trippy demos on an old Nokia color LCD. [Maarten]’s friend [Jeroen Domburg] (aka Sprite_tm) had a hand in creating most of the gadgets, and he’s someone whose brilliant work we have had the good fortune to feature many times in the past.