Much of the Northern Hemisphere is currently in the middle of winter, so what better way to brighten a potentially gloomy day than to put this charming, minimalist weather display on your desk.

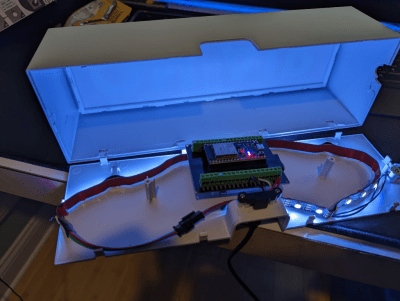

[Joe] has created a weather gauge that uses two servo motors to position mechanical pointers to indicate weather symbols and time ranges. The electronics consists of a push button and two SG90 servos driven by a Raspberry Pi Zero W 2. The case is 3D printed including the pointers attached to the servos and the button brim of the switch. The Raspberry Pi Zero W 2 is programmed to automatically connect to the OpenWeather API to retrieve the latest weather conditions, with the latitude and longitude being configured into the update script during the configuration and assembly stages.

[Joe] has provided extensive documentation about the build and software setup, in addition to releasing the source code and STL files for anyone wanting to make their own. [Joe] even offers kits for those who don’t want to go through the trouble of putting one together themselves — not that we imagine many in this particular audience would fall into that category.

We love to see these delightful weather builds and we’ve featured others in the past, like a converted weather house for weather prediction or a weather reporting diorama.

Continue reading “Let This Minimal Desktop Weather Display Point The Way”