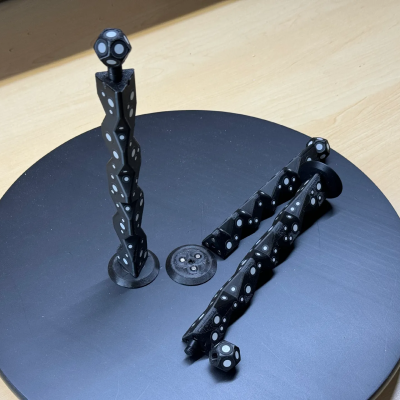

Apple AirTags have speakers in them, and the speaker is not entirely under the owner’s control. [Shahram] shows how the speaker of an AirTag can be disabled while keeping the device watertight. Because AirTags are not intended to be opened or tampered with, doing so boils down to making a hole in just the right place, as the video demonstrates.

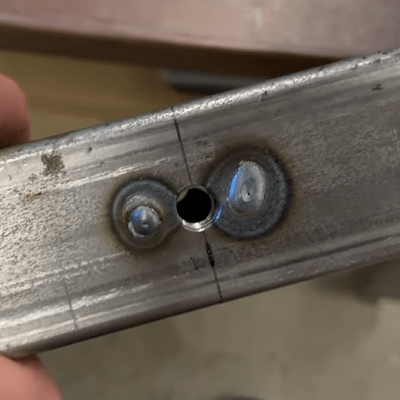

How does putting a hole in the enclosure not compromise water resistance? By ensuring the hole is made in an area that is already “inside” the seal. In an AirTag, that seal is integrated into the battery compartment.

Behind the battery, the enclosure has a small area of thinner plastic that sits right above the PCB, and in particular, right above the soldered wire of the speaker. Since this area is “inside” the watertight seal, a hole can be made here without affecting water resistance.

Disabling the speaker consists of melting through that thin plastic with a soldering iron then desoldering the (tiny) wire and using some solder wick to clean up. It’s not the prettiest operation, but there are no components nor any particularly heat-sensitive bits in that spot. The modification has no effect on water resistance, and isn’t even visible unless the battery is removed.

In the video below, [Shahram] uses a second generation AirTag to demonstrate the mod, then shows that the AirTag still works normally while now being permanently silenced.

Continue reading “AirTag Has Hole Behind The Battery? It’s Likely Been Silenced”