A basic digital multimeter (DMM) is usually the first measurement tool the aspiring electronics tinkerer buys. Even a bargain-bin DMM will happily measure voltage, current, and resistance; check continuity; and may even have a mode to measure transistor gain. Every toolbox needs at least one DMM, but most have an crucial limitation— they can’t measure two of the fundamental electrical quantities: inductance and capacitance. On Hackaday.io, [core weaver] has developed an open-source LC meter to allow you to build your own tool to measure inductance and capacitance.

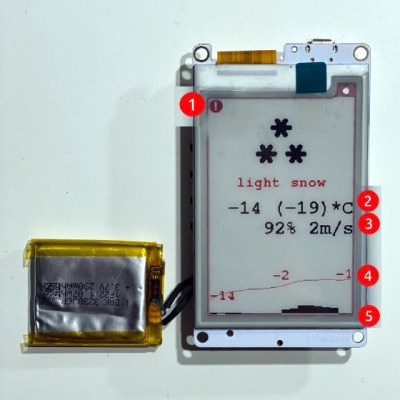

[core weaver]’s design is all through-hole, so even just assembling one would be a great exercise for someone getting started in electronics. However, he didn’t just release a design, in a series of videos he goes through the theory of the device’s operation; explains the design of the circuit, firmware, and case; and shows you how to put it all together. For times when you need to measure a lot of parts (e.g. if you have to sort a bag of cheap capacitors looking for specific value), he’s even developed a desktop program to save you some trouble!

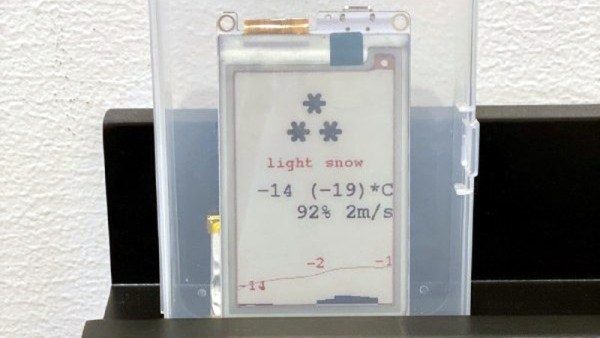

The finished meter looks incredible! If you want to build one for yourself, he’s put all of the files up on GitHub, and we highly recommend you check out his first video after the break. If you’d like to build yourself a 6.5-digit DMM to go with our LC Meter, consider this one which even has a home-built ADC.