There are some incredibly cheap WiFi smart bulbs on the market these days, but as is often the case, you tend to get what you pay for. When [Viktor] took delivery of his latest bargain basement bulb, the thing didn’t even work. So much for Quality Assurance. On the plus side, it was a great excuse to pop it open and replace the firmware.

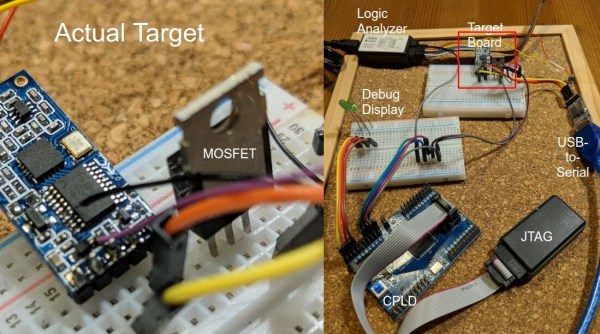

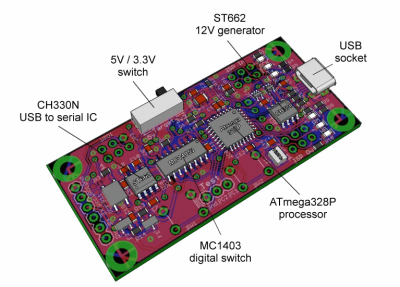

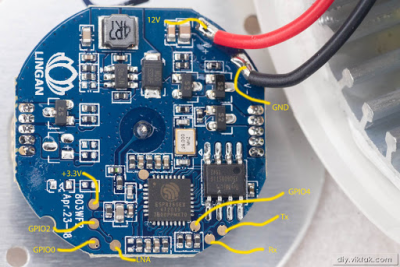

For anyone wondering, [Viktor] never actually figured out why the bulb didn’t work. Its ESP8266-based control board was getting power, and data was getting spit out of the serial port when he connected it to the computer (although he never got the communications settings right to actually see what it was saying). But he also didn’t care much; once he confirmed that the hardware was good, he just uploaded the custom firmware he’d previously developed for another ESP8266 bulb.

For anyone wondering, [Viktor] never actually figured out why the bulb didn’t work. Its ESP8266-based control board was getting power, and data was getting spit out of the serial port when he connected it to the computer (although he never got the communications settings right to actually see what it was saying). But he also didn’t care much; once he confirmed that the hardware was good, he just uploaded the custom firmware he’d previously developed for another ESP8266 bulb.

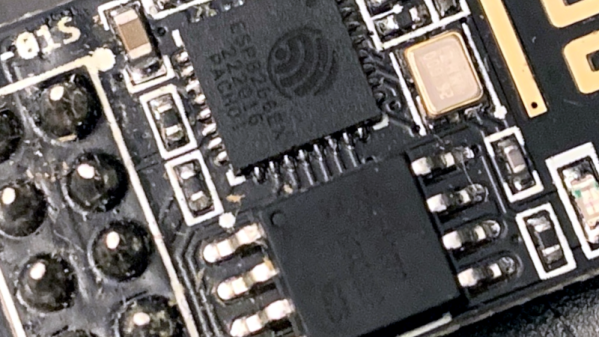

Of course, it wasn’t quite that easy. The chances that both bulbs would have used the same GPIO pins to control the red, green, blue, and white LEDs were pretty slim. But after some testing and modifications to the code, he was able to fire them up. The other issue was a bit trickier, as it turned out the bulb’s flash chip was too small to hold his firmware’s web configuration pages. So he had to break out the hot air gun and replace the SPI flash chip with something a bit roomier. We suppose he could have just made smaller web pages… but where’s the fun in that?

Even with the chip swap, this looks a lot easier than building your own smart bulbs from scratch. With so many cheap ESP8266 bulbs on the market, it seems there’s never been a better time to code your own home lighting solution.