Flicking a circuit breaker to power cycle hundreds of desktop computers inside interactive museum exhibits is hardly ideal. Computers tend to get cranky when improperly shutdown, and there’s an non-zero risk of data loss. However, financial concerns ruled out commercial computer management solutions, and manually shutting down each exhibit at the end of the day is not practical. Tasked with finding a solution, [Jeff Glass] mixed off-the-shelf UPS (uninterruptible power supply) hardware, a Featherwing and some Python to give the museum’s computer-run exhibits a fighting chance.

Without drastically changing the one-touch end-of-day procedure, the only way to properly shutdown the hundreds of computers embedded in the museum exhibits involved using several UPS units, keeping the PCs briefly powered on after the mains power was cut. This in itself solves nothing – while the UPS can trigger a safe shutdown via USB, this signal could only be received by a single PC. These are off-the-shelf consumer grade units, and were never intended to safely shut down more than one computer at a time. However, each 300 watt UPS unit is very capable of powering multiple computers, the only limitation is the shutdown signal and the single USB connection.

To get around this, the Windows task scheduling service was setup to be triggered by the UPS shutdown signal, which itself then triggered a custom Python script. This script then relays the shutdown signal from the UPS to every other computer in the museum, before shutting itself down for the evening.

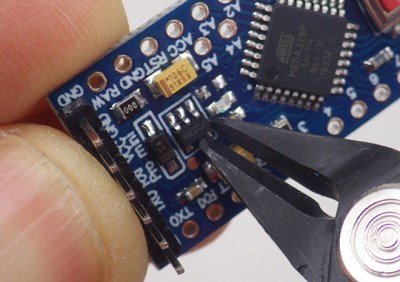

While many computers can be enabled to boot on power loss, the UPS and safe shutdown scripts meant that this wasn’t an option. To get around this, an ESP32 Featherwing and a little bit if CircuitPython code sends out WOL (wake-on-LAN) signals over Ethernet automatically on power up. This unit is powered by a non-UPS backed power outlet, meaning that it only sends the WOL signal in the morning when mains power is restored via the circuit breaker.

There are undoubtedly a variety of alternative solutions that appear ‘better’ on paper, but these may gloss over the potential costs and disruption to a multi-acre museum. Working within the constraints of reality means that the less obvious fix often ends up being the right one. How would you have tackled this problem? Sound off in the comments below. And while you’re here, make sure to check out our coverage of other UPS solutions, like this supercap UPS.