People trying to replicate their favorite items and gadgets from video games is nothing new, and with desktop 3D printing now at affordable prices, we’re seeing more of these types of projects than ever. At the risk of painting with too broad a stroke, most of these projects seem to revolve around weaponry; be it a mystic sword or a cobbled together plasma rifle, it seems most gamers want to hold the same piece of gear in the physical world that they do in the digital one.

But [Jonathan Whalen] walks a different path. When provided with the power to manifest physical objects, he decided to recreate the iconic “Question Block” from the Mario franchise. But not content to just have a big yellow cube sitting idly on his desk, he decided to make it functional. While you probably shouldn’t smash your head into the thing, if you give it a good knock it will launch gold coins into the air. Unfortunately you have to provide the gold coins yourself, at least until we get that whole alchemy thing figured out.

But [Jonathan Whalen] walks a different path. When provided with the power to manifest physical objects, he decided to recreate the iconic “Question Block” from the Mario franchise. But not content to just have a big yellow cube sitting idly on his desk, he decided to make it functional. While you probably shouldn’t smash your head into the thing, if you give it a good knock it will launch gold coins into the air. Unfortunately you have to provide the gold coins yourself, at least until we get that whole alchemy thing figured out.

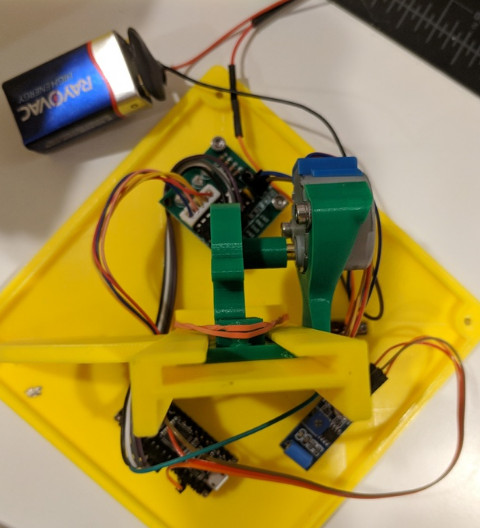

Printing the block itself is straightforward enough. It’s simply a 145 mm yellow cube, with indents on the side to accept the question mark printed in white and glued in. A neat enough piece of decoration perhaps, but not exactly a hack.

The real magic is on the inside. An Arduino Nano and a vibration sensor are used to detect when things start to get rough, which then sets the stepper motor into motion. Through an ingenious printed rack and pinion arrangement, a rubber band is pulled back and then released. When loaded with $1 US gold coins, all you need to do is jostle the cube around to cause a coin to shoot out of the top.

If this project has got you interested in the world of 3D printed props from the world of entertainment, don’t worry, we’ve got you covered.

Continue reading “Beat This Mario Block Like It Owes You Money”