If you take public transport in many of the world’s cities, your ticket will be an NFC card which you scan to gain access to the train or bus. These cards are disposable, so whatever technology they use must be astonishingly cheap. It’s one of these which [Ken Shirriff] has turned his microscope upon, a Montreal Métro ticket, and his examination of the MiFare Ultra Light it contains is well worth a read.

The cardboard surface can be stripped away from the card to reveal a plastic layer with a foil tuned circuit antenna. The chip itself is a barely-discernible dot in one corner. For those who like folksy measurements, smaller than a grain of salt. On it is an EEPROM to store its payload data, but perhaps the most interest lies in the support circuitry. As an NFC chip this has a lot of RF circuitry, as well as a charge pump to generate the extra voltages to charge the EEPROM. In both cases the use of switched capacitors plays a part in their construction, in the RF section to vary the load on the reader in order to transmit data.

He does a calculation on the cost of each chip, these are sold by the wafer with each wafer having around 100000 chips, and comes up with a cost-per-chip of about nine cents. Truly cheap as chips!

If NFC technology interests you, we’ve taken a deep dive into their antennas in the past.

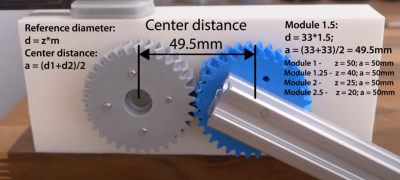

durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.

durability and increase noise. On the other hand, helical gears have a more gradual engagement, resulting in reduced noise and smoother operation. This leads to an increased load-carrying capacity, thus improving durability and lifespan.