It’s very likely indeed that whatever you are reading this on will have a multi-core processor. They’re now the norm, but the path to they octa-or-more-core chip in your phone has gone from individual processors with PCB interconnects through many generations of ever faster on-chip ones.

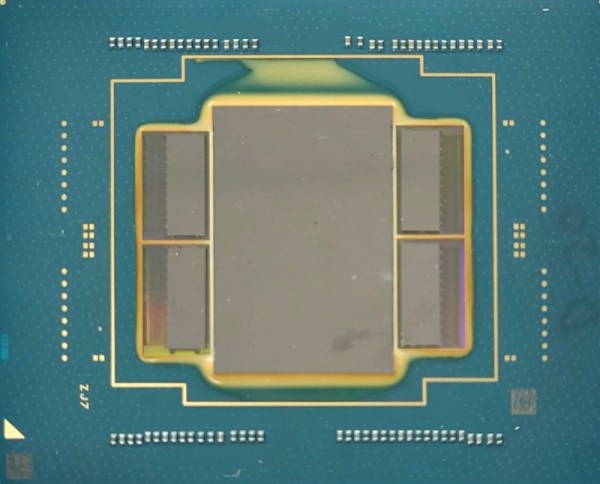

But what if your power needs are so high-end that you need more cores that can be fitted on one chip, but without the slow PCB interconnect to another? If you’re Intel, you develop a multi-core processor with an on-chip photonic interconnect. It talks to the neighboring ones in its cluster at full speed, via light.

The chip in question isn’t one you’ll see in a machine near you, instead it’s inspired by the extremely demanding requirements for DARPA’s HIVE graph analytics program. So this is a machine for supercomputers in huge data centers rather than desktop computers, it will be assembled into multi-die packages with that chip-to-chip optical networking built in. But your computer today is the equal of a supercomputer from not that many years ago, so never say you won’t one day be using its descendant technologies.