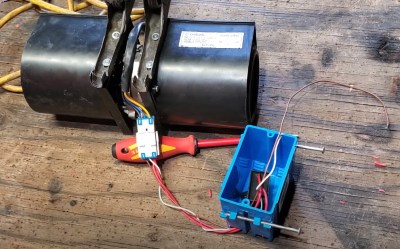

At this point, somebody taking the motors out of a cheap “hoverboard” and using them to power a scooter or remote controlled vehicle isn’t exactly a new idea. But in the case of the FPV rover [Proto G] has been working on, his choice of motors is only part of the story. The real interesting bit is the 3D printed omnidirectional Mecanum wheels he’s designed to fit the motors, which he thinks could have far reaching applications beyond his own project.

Now, that isn’t to say that the rover itself isn’t impressive. All of the laser cutting and sheet metal bending was done personally by [Proto G], and we love the elevated GoPro “turret” in the front that lets him look around while remotely driving the vehicle. Powered by a pair of Makita cordless tool batteries and utilizing hobby-grade RC parts, the rover looks like it would be a fantastic robotic platform to base further development on.

Now, that isn’t to say that the rover itself isn’t impressive. All of the laser cutting and sheet metal bending was done personally by [Proto G], and we love the elevated GoPro “turret” in the front that lets him look around while remotely driving the vehicle. Powered by a pair of Makita cordless tool batteries and utilizing hobby-grade RC parts, the rover looks like it would be a fantastic robotic platform to base further development on.

The Mecanum wheels themselves are two pieces, and make use of rollers pulled from far smaller commercially available wheels. This is perhaps not the most cost effective approach, but compared to the alternative of trying to print all the rollers, we see the advantage of using something off-the-shelf. If you’re not sure how to make these weird wheels work for you, [Proto G] has also released a video explaining how he mixes the RC channels to get the desired omnidirectional movement from the vehicle.

If you’re content with more traditional wheeled locomotion, we’ve previously seen how quickly a couple of second-hand hoverboards can be turned into a impressively powerful mobile platform for whatever diabolical plans you may have.

Continue reading “3D Printed Mecanum Wheels For Hoverboard Motors”