Usually when we post a Fail Of The Week, it’s a heroic tale of a project made with the best of intentions that somehow failed to hit its mark. The communicator that didn’t, or the 3D-printed linkage that pushed the boundaries of squirted plastic a little bit too far. But today we’re bringing you something from a source that should be above reproach, thanks to [Boldport] bringing us a Twitter conversation between [Stargirl] and [Ticktok] about a Texas Instruments datasheet.

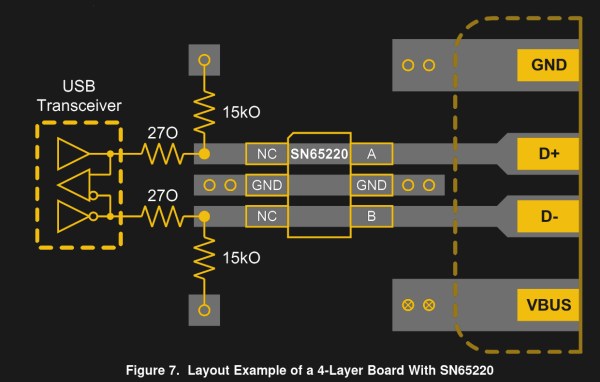

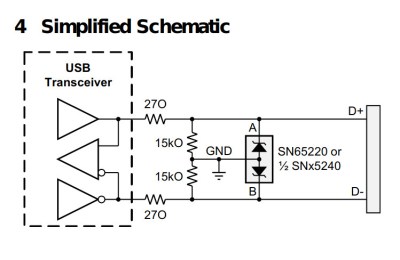

The SN65220 is a suppressor chip for USB ports, designed to protect whatever the USB hardware is from voltage spikes. You probably have several of them without realising it, the tiny six-pin package nestling on the PCB next to the USB connector. Its data sheet reveals that it needs a resistor network between it and the USB device it protects, and it’s this that is the source of the fail.

There are two resistors, a 15kO and a 27O, 15k ohms, and 270 ohms, right? Looking more closely though, that 27O is not 270 with a zero, but 27O with a capital “O”, so in fact 27 ohms.

The symbol for resistance has for many decades been an uppercase Greek Omega, or Ω. It’s understood that sometimes a typeface doesn’t contain Greek letters, so there is a widely used convention of using an uppercase “R” to represent it, followed by a “K” for kilo-ohms, an “M” for mega-ohms, and so on. Thus a 270 ohm resistor will often be written as 270R, and 270 kilo-ohm one as 270K. In the case of a fractional value the convention is to put the fraction after the letter, so for example 2.7kilo-ohms becomes 2K7. For some reason the editor of the TI datasheet has taken it upon themselves to use an uppercase “O” to represent “Ohms”, leading to ambiguity over values below 1 kilo-ohm.

We can’t imagine an engineer would have made that choice so we’re looking towards their publishing department on this one, and meanwhile we wonder how many USB devices have gone to manufacture with a 270R resistor in their data path. After all, putting the wrong resistor in can affect any of us.