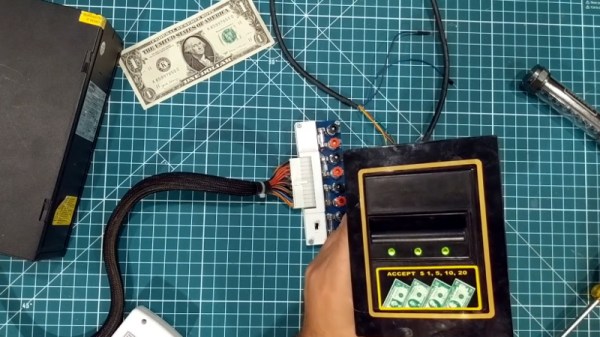

We’ve all seen, and occasionally wrestled with, bill acceptors like the one [Another Maker] recently liberated from an arcade machine. But have you ever had one apart to see how it works? If not, the video after the break is an interesting peak into how this ubiquitous piece of hardware tells the difference between a real bill and a piece of paper.

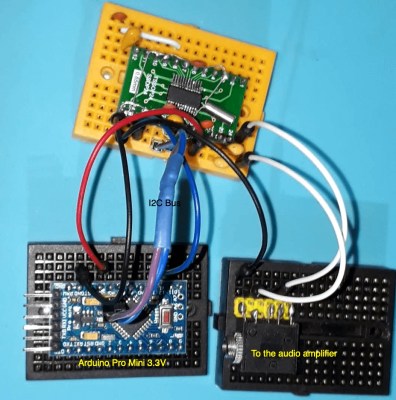

But [Another Maker] goes a bit farther than just showing the internals of the device. He also went through the trouble of figuring out how to talk to it with an Arduino, which makes all sorts of money-grabbing projects possible. Even if collecting paper money isn’t your kind of thing, it’s still interesting to see how this gadget works on a hardware and software level.

But [Another Maker] goes a bit farther than just showing the internals of the device. He also went through the trouble of figuring out how to talk to it with an Arduino, which makes all sorts of money-grabbing projects possible. Even if collecting paper money isn’t your kind of thing, it’s still interesting to see how this gadget works on a hardware and software level.

As explained in the video, a set of belts are used to pull the bill past an array of IR LEDs. The hardware uses these to scan the bill and perform some dark magic to determine if it’s a genuine piece of currency. [Another Maker] notes that these readers actually need to receive occasional firmware updates to take into account new bill designs. In fact, the particular unit he has is so out of date that it won’t accept modern $5 bills; which may explain how he got it for free in the first place.

Years ago we saw one of these bill acceptors used to make a DIY Bitcoin ATM. Of course back then, a few bucks would get you a semi-reasonable amount of BTC. These days you would skip the paper currency and do it all digitally.

Continue reading “Using A Vending Machine Bill Acceptor With Arduino”