Many arcade machines can be emulated and handily controlled with the standard joystick and button combos. However, a few don’t feel quite right without some extra equipment, motorcycle racing games being one of them. So, no longer content to go to an arcade to get his fix, [The Q] welded his own motorcycle simulation rig for playing racing games at home.

After an initial design was sketched out, rectangular tube steel was cut to size and welded together with a MIG welder. A central shaft linked to some secured bearings made the central pivot point. A few pistons offered the resistance needed for leaning into the curves. To the central shaft, a seat and an old bicycle fork were attached. A clever linkage from the handlebars to the base causes the bike to tilt when turning the handlebars and vice versa.

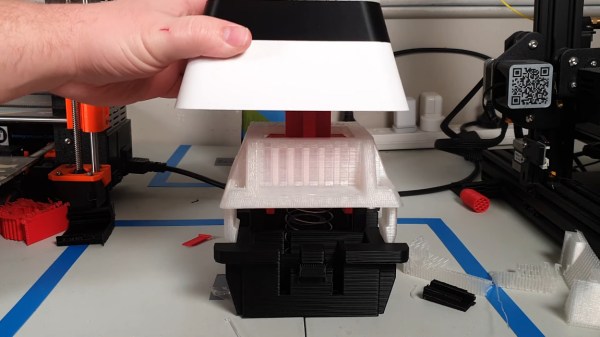

The bike was ready for prime time after some grinding, orange paint, a license plate, and some lights and grips. [The Q] just needed to get the angle of the bike into the simulation of their choice. While we expected a teensy or other microcontroller emulating a controller, [The Q] went for a somewhat simpler approach, and 3D printed a cradle to hold a PlayStation controller. Little levers pull strings to articulate the joystick, and a cable from the throttle grip pulls back the trigger on the controller. All in all, the experience looks pretty decent, particularly when you’re comparing it to a motocross arcade machine. What it really needs are some fans blowing for the effect of the air stream coming at you.

If you’re thinking about busting out the MIG to make a rig of your own, maybe consider making a homemade car racing rig to complement the bike.

Continue reading “Motorcycle Simulation Rig Is Off To The Races”

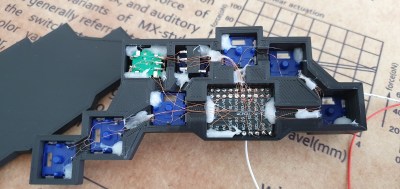

![[deshipu]'s DIY keyboard with various center modules](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/deʃhipu-Kamina.png?w=400)