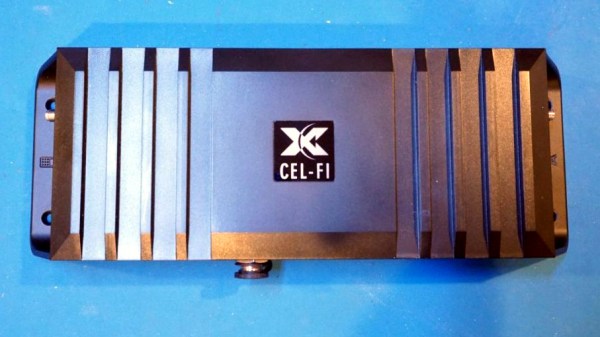

Ever wonder what was inside a cell phone booster, or what it is like to set up or use one? If so, [Kerry Wong]’s got you covered with his teardown of a Cel-Fi Go X Cell Signal Booster by Nextivity. [Kerry] isn’t just ripping apart a cheap unit for laughs; his house has very poor reception and this unit was a carefully-researched, genuine investment in better 4G connectivity.

The whole setup consists of three different pieces: the amplifier unit pictured above, and two antennas. One is an omnidirectional dome antenna for indoors, and the other is a directional log-periodic dipole array (LPDA) antenna for outdoors. Mobile phones connect to the indoor antenna, and the outdoor antenna connects to the distant cell tower. The amplifier unit uses a Bluetooth connection and an app on the mobile phone to manage settings and actively monitor the device, which works well but bizarrely doesn’t seem to employ any kind of password protection or access control whatsoever.

Overall [Kerry] is happy, and reports that his mobile phone enjoys a solid connection throughout his house, something that was simply not possible before. Watch a hands-on of the teardown along with a short demonstration in the video embedded below.

Continue reading “Cell Phone Signal Booster Gets Teardown And Demo”