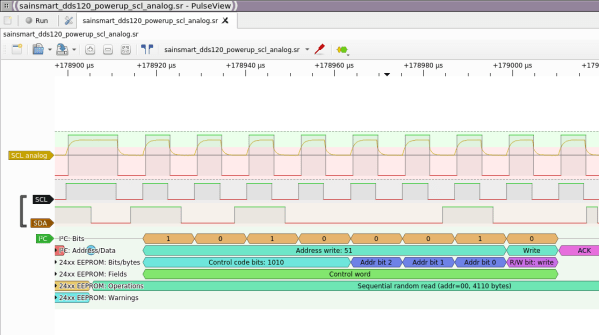

There’s a slew of hardware hacker problems that a logic analyzer is in a perfect position to solve. Whether you’re trying to understand why an SPI LCD screen doesn’t initialize, what’s up with your I2C bus, or determine the speed of an UART connection, you’ll really want to have a logic analyzer on hand. People have been using a Pi Pico as a logic analyzer in a pinch, and now [pico-coder] has shared a sigrok driver that adds proper support for a Pico to beloved tools like Pulseview.

The specs offered are impressive. Compared to the $10 “Saleae” clone analyzers we are so used to, this thing boasts 21 digital channels with up to 120 MHz capture speed, 3 ADC channels at up to 500 KHz, and hardware-based triggers. The GitHub repository linked above stores the driver files out-of-tree, but provides build instructions together with an easily flash-able uf2 firmware. It’s likely that you’ll soon see this driver in a stock Pulseview installation, however, given the submitter-friendly attitude we’ve witnessed on the sigrok mailing list. However, if you need a logic analyzer ASAP, you should follow the caringly offered quickstart guide.

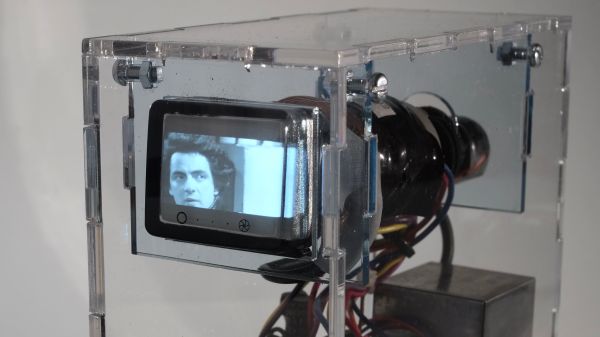

We’ve covered Pulseview being used in combination with cheap accessible analyzers before — a must-watch if you need to get yourself up to speed on the value they provide to a hobbyist. If an oscilloscope is what you need and a smartphone is what you have, perhaps you’ll enjoy the Scoppy firmware for the Pico.

We thank [mip] for sharing this with us!