We imagine most of the people reading Hackaday have an old Raspberry Pi or two laying around. It’s somewhat less likely you’ve still got an 8-bit Commodore in working condition, but we’d wager there’s more than a few in the audience that can count themselves among both groups. So why not introduce them?

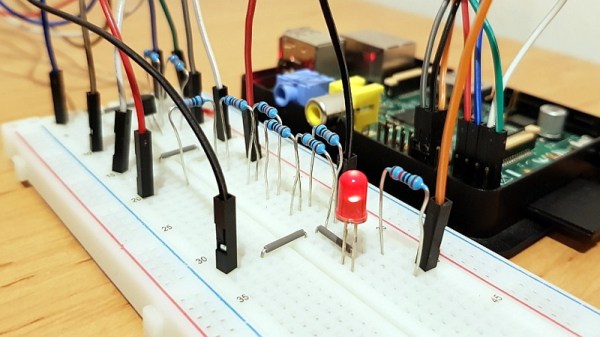

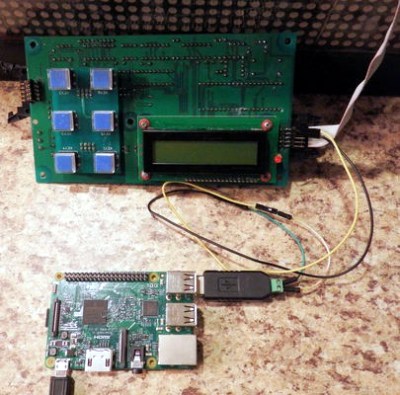

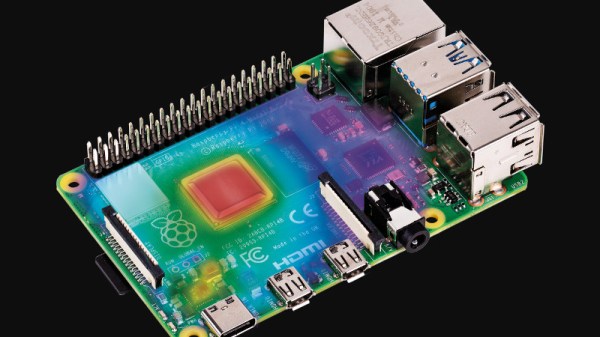

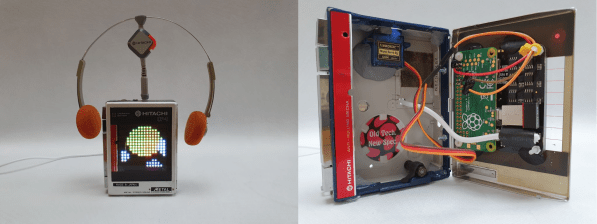

[RhinoDevel] writes in to tell us about CBM Tape Pi , an open source Commodore tape drive emulator for Raspberry Pi that needs only a handful of passive components to get wired up. Even better, the project targets the older Pis that are more likely to be languishing around in the parts bin. In the video after the break, a Commodore PET can be seen happily loading content from the original Raspberry Pi with its quaint little composite video connector.

Without any special software on the Commodore itself, the project allows the user to load and save PRGs on the Pi’s SD card, as well as traverse directories. Don’t expect stellar I/O, as [RhinoDevel] notes that no fast loader is currently implemented. Of course if you’re enough of a devotee to still be poking around a VIC-20 or C64 this far into 21st century, then we imagine you’ve got enough patience to get by.

Continue reading “Commodore Tape Drive Emulator On A Raspberry Pi”