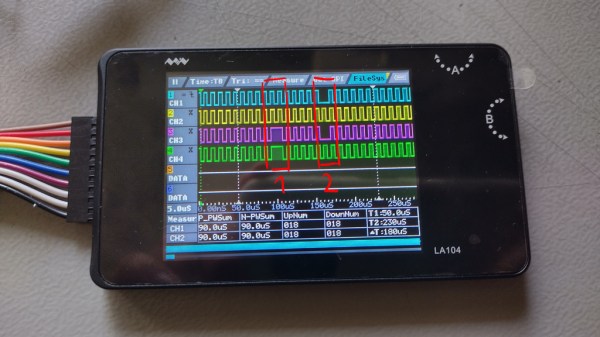

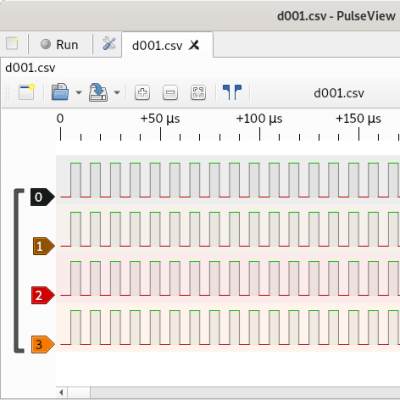

[Avian] has picked up a Miniware LA104 – a small battery-powered logic analyzer with builtin protocol decoders. Such analyzers are handy tools for when you quickly need to see what really is happening with a certain signal, and they’re cheap enough to be sacrificial when it comes to risky repairs. Sadly, he stumbled upon a peculiar problem – the analyzer would show the signal glitching every now and then, even at very low bitrates. Even more surprisingly, the glitches didn’t occur in the signal traces when exported and viewed on a laptop.

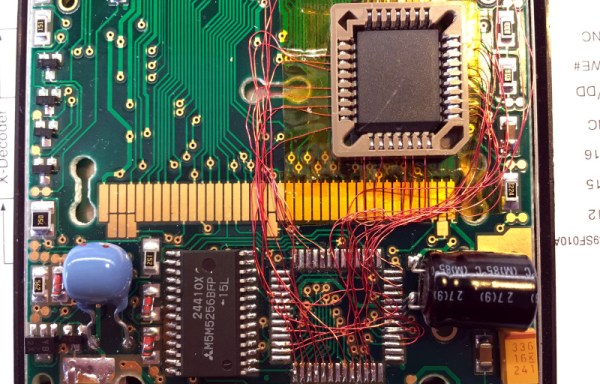

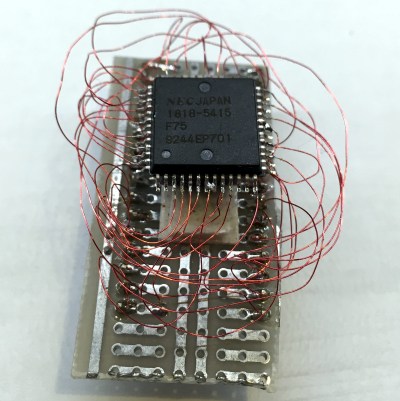

He dug into the problem, as [Avian] does. Going through the problem-ridden capture files helped him realize that the glitch would always happen when one of the signal edges would be delayed by a few microseconds relative to other signal edges — a regular occurrence when it comes to digital logic. This seems to stem from compression being used by the FPGA-powered “capture samples and send them” part of the analyzer. This bug only relates to the signal as it’s being displayed on the analyzer’s screen, and turned out that while most of this analyzer’s interface is drawn by the STM32 CPU, the trace drawing part specifically was done by the FPGA using a separate LCD interface.

He dug into the problem, as [Avian] does. Going through the problem-ridden capture files helped him realize that the glitch would always happen when one of the signal edges would be delayed by a few microseconds relative to other signal edges — a regular occurrence when it comes to digital logic. This seems to stem from compression being used by the FPGA-powered “capture samples and send them” part of the analyzer. This bug only relates to the signal as it’s being displayed on the analyzer’s screen, and turned out that while most of this analyzer’s interface is drawn by the STM32 CPU, the trace drawing part specifically was done by the FPGA using a separate LCD interface.

It would appear Miniware didn’t do enough testing, and it’s impossible to distinguish a good signal from a faulty one when using a LA104 – arguably, the primary function of a logic analyzer. In the best of Miniware traditions, going as far as being hostile to open-source firmware at times, the FPGA bistream source code is proprietary. Thus, this bug is not something we can easily fix ourselves, unless Miniware steps up and releases a gateware update. Until then, if you bought a LA104, you can’t rely on the signal it shows on the screen.

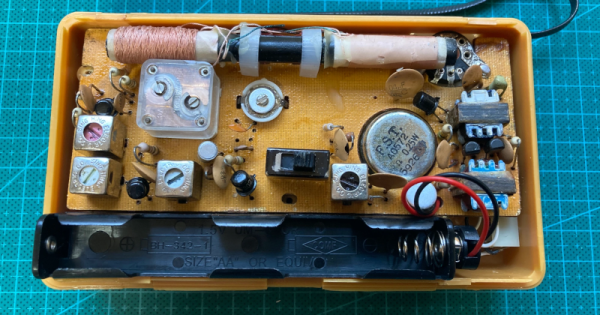

When it comes to Miniware problems, we’ve recently covered a Miniware tweezer repair, requiring a redesign of the shell originally held together with copious amount of glue. At times, it feels like there’s something in common between glue-filled unrepairable gadgets and faulty proprietary firmware. If this bug ruins the LA104 for you, hey, at least you can reflash it to work as an electronics interfacing multitool.