On modern desktop and laptop computers, there is rarely a need to think about memory. We all have many gigabytes of the stuff, and it’s just there. Our operating system does the heavy lifting of working out what goes where and what needs to be paged to disk, and we just get on with reading Hackaday, that noblest of computing pursuits. This was not always the case though, and for early PCs in particular the limitations of the 8086 processor gave the need for some significant gymnastics in search of an extra few kilobytes. [Julio Merion] has an interesting run-down of the DOS memory map, and how memory expansion happened on computers physically unable to see much of it.

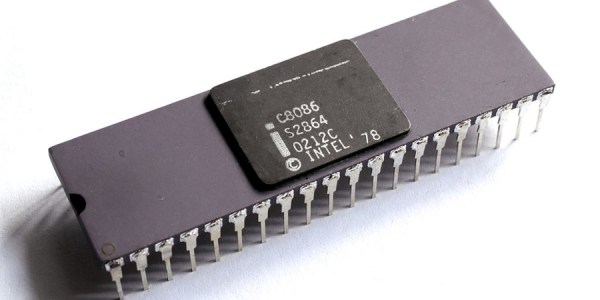

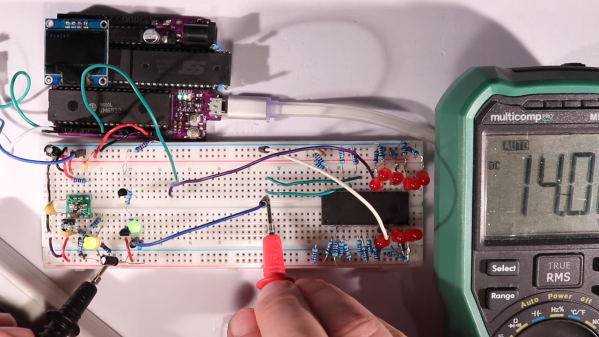

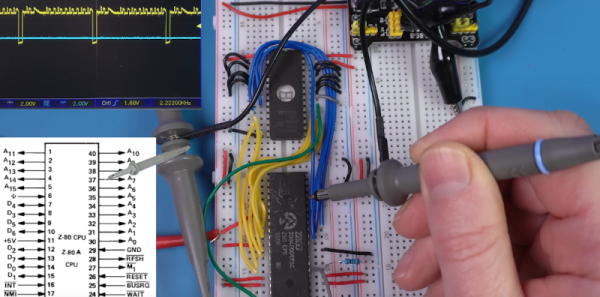

The 8086 has a 20-bit address bus, giving it access to a maximum of 1 megabyte. When IBM made the PC they needed space for the BIOS, the display, and the various accessory ROMs intended to come with expansion cards. Thus they allocated a maximum 640k of the map for RAM, and many early machines shipped with much less than that. The quote from Bill Gates about 640k being enough for anyone is probably apocryphal, but it was pretty clear as the 1980s wore on that more would be needed. The post goes into how memory expansion worked, with a 64k page mapped to switchable RAM on a card, and touches on how DOS managed extended memory above 1 Mb on the later processors that supported it. We dimly remember there also being a device driver that would map the unused graphics memory as EMS when the graphics card was running in text mode, but such horrors are best left behind.

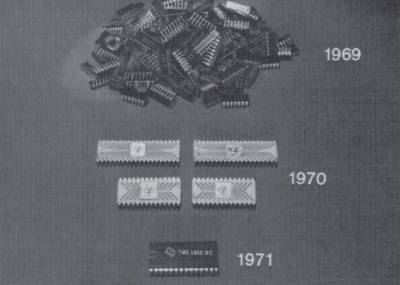

Of course, some of the tricks to boost RAM were nothing but snake oil.

8086 header: Thomas Nguyen, CC BY-SA 4.0