Thirty years ago, [Robert “Buz” Chmielewski] suffered a surfing accident as a teenager. This left him as a quadriplegic due to a C6 spinal cord injury. After becoming a participant in a brain-computer interface study at Johns Hopkins, he was recently able to feed himself through the use of prosthetic arms. The most remarkable thing about these prosthetic arms is primarily the neural link with [Buz’s] brain, which allows him to not only control the artificial arms, but also feel what they are touching, due to a closed-loop system which transfers limb sensory input to the patient’s brain.

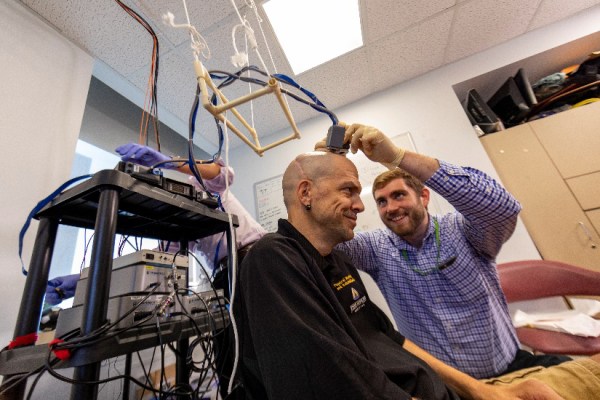

The prosthetic limb in question is the Modular Prosthetic Limb (MPL) from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). The Johns Hopkins Medicine Brain-Computer Interface study began a year ago, when [Buz] had six microelectrode arrays (MEA) implanted into his brain: half in the motor cortex and half in the sensory cortex. During the following months, the study focused on using the signals from the first set of arrays to control actuators, such as the MPL. The second set of arrays was used to study how the sensory cortex had to be stimulated to allow a patient to feel the artificial limb much as one feels a biological limb.

What makes this study so interesting is not only the closed-loop approach which provides the patient with feedback on the position and pressure on the prosthetic, but also that it involves both hemispheres of the brain. As a result, after only a year of the study, [Buz] was able to use two of the MPLs simultaneously to feed himself, which is a delicate and complicated tasks.

In the video embedded after the break one can see a comparison of [Buz] at the beginning of the study and today, as he manages to handle cutlery and eat cake, without assistance.