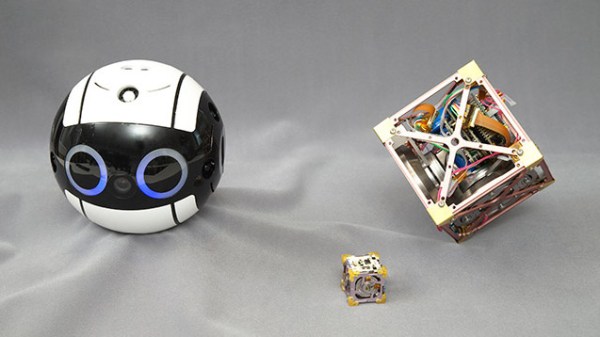

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) recently contributed their Int-Ball technology to a Kickstarter campaign operated by the Japanese electronics manufacturer / distributor Bit Trade One (Japanese site). This technology is based on the Cubli project out of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH Zurich), which we covered back in 2013. The Cubli-based technology has been appearing in various projects since then, including the Nonlinear Mechatronic Cube in 2016. Alas, the current JAXA-based “3-Axis Attitude Control Module” project doesn’t have a catchy name — yet.

One interesting application of these jumping cubes, presumably how JAXA got involved with these devices, is a floating video camera that was put to use on board the International Space Station (ISS) in 2017. The version being offered by the Kickstarter campaign doesn’t include the cameras, and you will need to provide your own a gravity-free environment to duplicate that application. Instead, they seem to be marketing this for educational uses. You’d better dig deep in your wallet if you want one — a fully assembled unit requires a pledge of over $5000 ( there is a “some assembly required” kit that can save you about $1000 ). Most of us won’t be backing this project for that reason alone, but it is nice to see the march of progress of such a cool technology: from inception to space applications to becoming available to the general public. Thanks to [Lincoln Uehara] for sending in this tip.