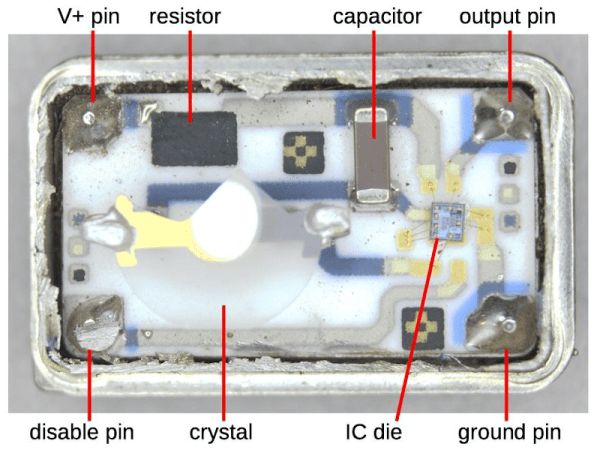

We are always glad to see [Ken Shirriff] tear into something new and this month he’s looking inside a quartz oscillator module. Offhand, you’d think there’s not much to these. A slab of quartz and some sort of inverter, right? But as [Ken] mentions, “There’s more happening in the module than I expected…”

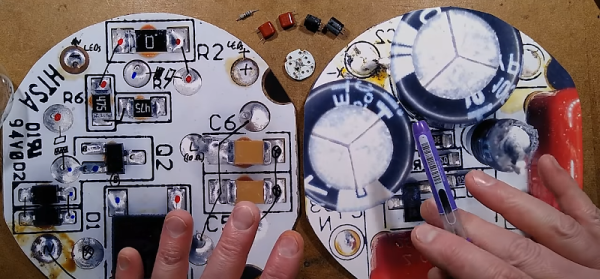

If you’ve ever wanted to decap devices, big hybrid modules like these are a good way to get started since you don’t need exotic chemicals to get at the insides. [Ken] managed to break the fragile crystal wafer on the way in. Inside was also a small CMOS IC die. Time to get out the microscope.

If you follow [Ken’s] blog, you know he’s no stranger to analyzing IC dice. The oscillator IC is a pretty standard Colpitts oscillator but it also provides a programmable divider and output drive.

The circuit uses some unusually configured capacitors. [Ken] takes the time to point out CMOS logic structures throughout. If you haven’t seen one of [Ken’s] deep dives before, before, it’s a great introduction.

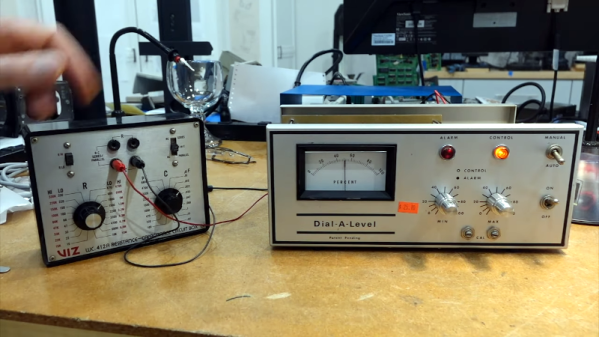

You can learn more about crystal oscillator theory. We used some test equipment to characterize a crystal a few years ago.