The last challenge of The Hackaday Prize has just ended. Over the past few months, we’ve gotten a sneak peek at over a thousand amazing projects, from Open Hardware to Human Computer Interfaces. This is a contest, though, and to decide the winner, we’re tapping some of the greats in the hardware world to judge these astonishing projects.

Below are just a preview of the judges in this year’s Hackaday Prize. In the next few weeks, we’ll be sending the judging sheets out to them, tallying the results, and in just under a month we’ll be announcing the winners of the Hackaday Prize at the Hackaday Superconference in Pasadena. This is not an event to be missed — not only are we going to hear some fantastic technical talks from the hardware greats, but we’re also going to see who will walk away with the Grand Prize of $50,000.

Kipp Bradford

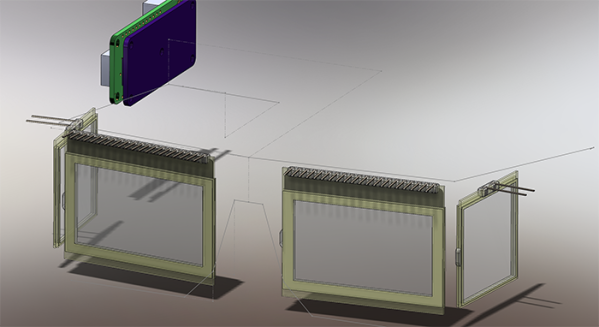

Kipp Bradford is a biomedical engineer and Research Scientist at the MIT Media Lab. His work focuses on reinventing cool. He is a leader in the maker movement and has founded a variety of start-ups. He was a presenter at the Hackaday Superconference last year where he talked about the importance of building boring projects. It’s a great talk about Devices for Controlling Climates, or quite simply, an HVAC system. This isn’t a flashy project by any means — refrigeration has been around for a hundred years, and air conditioning has been common for fifty. Still, there’s a lot to learn about building infrastructure, and given the ubitquity of climate control systems, small efficiency gains can add up to a huge impact.

Madison Maxey

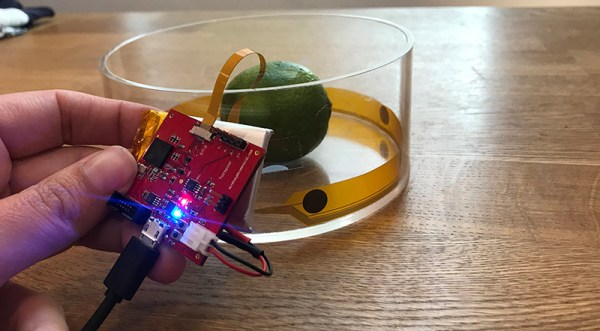

Madison Maxey is a internationally renowned technologist and multidisciplinary creative. Maxey has pioneered work in bringing flexible, robust circuitry to scale as Founder of LOOMIA, a technology that implants coats and jackets with soft, flexible circuitry that can heat, light, sense and track data. If you’re looking for wearable technology that isn’t made of copper and Kapton, look no further. LOOMIA has been featured by Business Insider, Forbes, and Huffington Post. This little bit of hardware can serve as a heater, keeping you warm, or as lighting to illuminate the headliner of a car or keep you visible at night. Maddy is a member of Forbes 30 under 30, a Thiel Fellow, and a Lord and Taylor Rose Award recipient.

Mark Rober

Mark Rober

Mark Rober is a former NASA engineer, an inventor, and current YouTuber with nearly three million subscribers, all of them interested in science and engineering. He’s been featured on Hackaday numerous times for engineering the perfect throw for skipping a rock across a lake, filling a hot tub with sand, then swimming in it, building a dart board that always catches your dart for the perfect bullseye, and building the world’s largest Super Soaker (yes, it’s the classic, original Super Soaker). His work has been featured in dozens of publications around the Internet. Mark is full of awesome ideas and through his YouTube channel is able to explain science and engineering clearly to millions of people around the globe.

Colin Furze

Colin Furze

Colin Furze is a mad Englishman in a shed who was formerly a plumber and now creates amazing inventions and incredible vehicles. His YouTube channel has over five million subscribers and his videos have been viewed over six hundred million times. He’s built a real hoverbike which must someday be taken to the forest moon of Endor, the world’s fastest bumper car that is also remarkably unsafe to actually use as a bumper car, and a knife that toasts bread as you slice it. But of course his most impressive achievement is gigantic pulse jet that was heard across the English Channel. And all of this without scorching his safety tie.

These are just four of the amazingly accomplished judges we have lined up to determine the winner of this year’s Hackaday Prize. The winner will be announced on November 3rd at the Hackaday Superconference. There are still tickets available, and you really want to be there if you can make it. Still, we’re going to be live streaming everything, including the prize ceremony, where one team will walk away with the grand prize of $50,000. It’s not an event to miss.

Mark Rober

Mark Rober