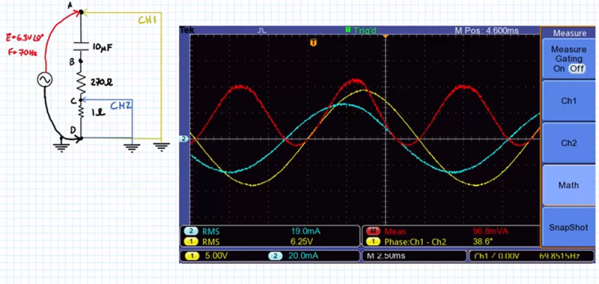

If you want to measure voltage you reach for a voltmeter. Current? An ammeter. Resistance? An ohmmeter. But what about measuring AC power? A watt meter? Usually. But if you know what to do, you could also reach for your oscilloscope. If you don’t know what to do, [Jim Pytel] has the video answers for you. Truth is, an oscilloscope can measure almost anything if you know how. [Jim] shows how to measure the voltage and current in a circuit and then it is simply a matter of doing a little math, something modern scopes can do very easily.

We like that [Jim] shows a circuit and how the math works before he verifies the math with the scope. Of course, theory doesn’t always match practice. The method uses a small current-sensing resistor that throws readings off a bit. The scope and signal generator are not perfect, either. However, the results match up pretty nicely with the computed results.