Laser aficionado [Martin Raynsford] has built up experience with various laser cutters over the years and felt he should write up a blog post detailing his first-hand findings with an often overlooked aspect of the machines: aiming them. Cheap diode laser cutters and engravers operate in the visible part of the spectrum, but when you get into more powerful carbon dioxide lasers such as the one used in the popular K40 machines, the infrared beam is invisible to the naked eye. A secondary low-power laser helps to visualize the main laser’s alignment without actually cutting the target. There are a couple of ways to install an aiming system like this, but which way works better?

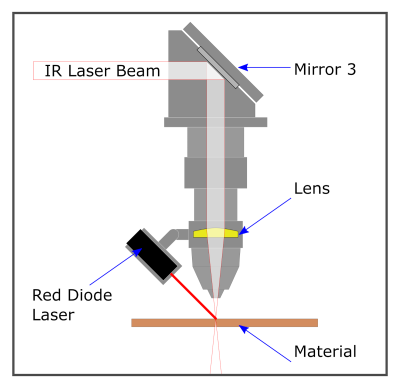

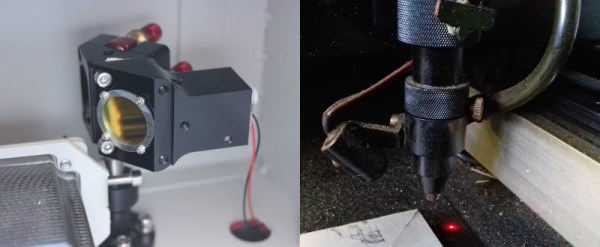

[Martin] explains that there are basically two schools of thought: a head-mounted laser, or a beam combiner. In both cases, a small red diode laser (the kind used in laser pointers) is used to indicate where the primary laser will hit. This allows the user to see exactly what the laser cutter will do when activated, critically important if you’re doing something like engraving a device and only have one chance to get it right. Running a “simulation” with the red laser removes any doubt before firing up the primary laser.

[Martin] explains that there are basically two schools of thought: a head-mounted laser, or a beam combiner. In both cases, a small red diode laser (the kind used in laser pointers) is used to indicate where the primary laser will hit. This allows the user to see exactly what the laser cutter will do when activated, critically important if you’re doing something like engraving a device and only have one chance to get it right. Running a “simulation” with the red laser removes any doubt before firing up the primary laser.

That’s the idea, anyway. In his experience, both methods have their issues. Head-mounted lasers are easier to install and maintain, but their accuracy changes with movement of the machine’s Z-axis: as the head goes up and down, the red laser dot moves horizontally and quickly comes out of alignment. Using the beam combiner method should, in theory, be more accurate, but [Martin] notes he’s had quite a bit of trouble getting both the red and IR lasers to follow the same course through the machine’s mirrors. Not only is it tricky to adjust, but it’s also much more complex to implement and may even rob the laser of power due to the additional optics involved.

In the end, [Martin] doesn’t think there is really a clear winner. Neither method gives 100% accurate results, and both are finicky, though in different scenarios. He suggests you just use whatever method your laser cutter comes with from the factory, as trying to change it probably isn’t worth the effort. But if your machine doesn’t have anything currently, the head-mounted laser is certainly the easier one to retrofit.

In the past, we’ve covered a third and slightly unconventional way of aiming the K40, as well as a general primer for anyone looking to pick up eBay’s favorite laser cutter.

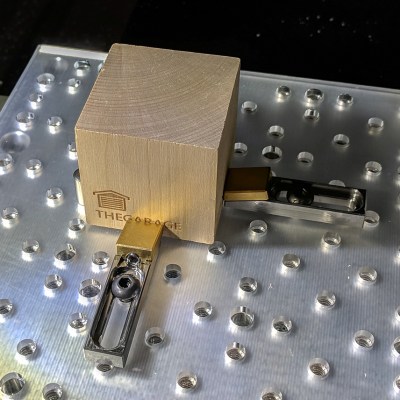

The usual way to secure a piece of stock to a fixturing table is to use top-down clamps, which hold the workpiece from the top and screw down into the table. However, this method limits how much of the stock can be accessed by the cutting tool, because the clamps are in the way. The most common way around this is to mount a vise to the table and clamp the workpiece in that. This leaves the top surface completely accessible. Unfortunately, [Kevin]’s benchtop Roland MDX-450 has a limited work area and he simply couldn’t spare the room. His solution was toe clamps, which screw down to the table and have little tabs that move inwards and downward. The tabs do the work of clamping and securing a piece of stock while maintaining a very low profile themselves.

The usual way to secure a piece of stock to a fixturing table is to use top-down clamps, which hold the workpiece from the top and screw down into the table. However, this method limits how much of the stock can be accessed by the cutting tool, because the clamps are in the way. The most common way around this is to mount a vise to the table and clamp the workpiece in that. This leaves the top surface completely accessible. Unfortunately, [Kevin]’s benchtop Roland MDX-450 has a limited work area and he simply couldn’t spare the room. His solution was toe clamps, which screw down to the table and have little tabs that move inwards and downward. The tabs do the work of clamping and securing a piece of stock while maintaining a very low profile themselves.