Once in a while there comes a time that you need a tool for one specific job. In these cases, it doesn’t make much sense to buy an expensive tool to use just once or twice. For most of us, Spot Welders would fall into this category. [mrjohngoh] had the need to join two pieces of sheet metal. Instead of purchasing a commercial unit, he set out to make his own spot welder.

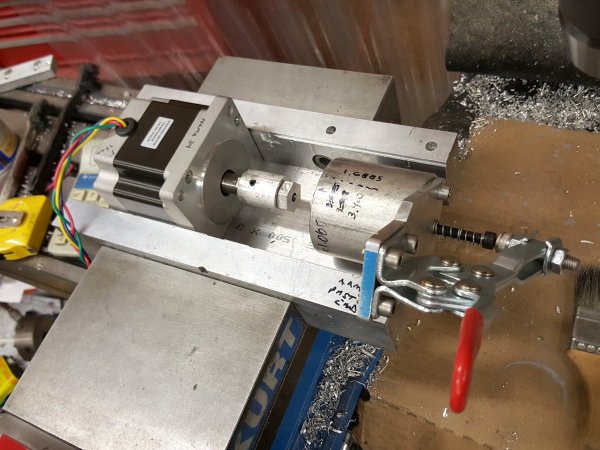

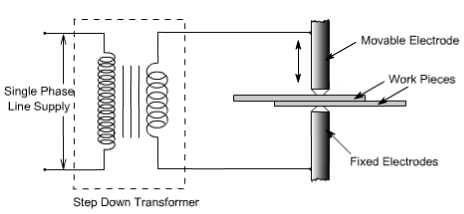

A spot welder works by passing an electric current through two thin pieces of metal. The resistance of the metal work pieces and the current passed though them creates enough heat to melt and join the two together at a single spot. To be able to get the high current needed for this project, [mrjohngoh] started with an old microwave transformer. He removed the standard secondary coil and re-wrapped it with 1cm thick wiring to get maximum current out of the transformer. The ends of the coil wire attach to electrodes, which are made from a high-current electrical plug. The electrodes are mounted at the ends of a pair of hinged arms. The weld is made when the two pieces of metal are sandwiched between the electrodes and power is applied.

A spot welder works by passing an electric current through two thin pieces of metal. The resistance of the metal work pieces and the current passed though them creates enough heat to melt and join the two together at a single spot. To be able to get the high current needed for this project, [mrjohngoh] started with an old microwave transformer. He removed the standard secondary coil and re-wrapped it with 1cm thick wiring to get maximum current out of the transformer. The ends of the coil wire attach to electrodes, which are made from a high-current electrical plug. The electrodes are mounted at the ends of a pair of hinged arms. The weld is made when the two pieces of metal are sandwiched between the electrodes and power is applied.

Spot welding isn’t just for joining two pieces of sheet metal. It’s also used for things like welding tabs onto battery terminals. The versatility and easy of building these welders make them one of the most featured tool hack we’ve ever seen.