The engineers and product designers at [moovel lab] have created the Open Data Cam – an AI camera platform that can identify and count objects as they move through its field of view – along with an open source guide for making your own.

Step one: get out your ruler and utility knife. In this world of ubiquitous 3D-printers they’ve taken a decidedly low-tech approach to the project’s enclosure: a cut, folded, and zip-tied plastic box, with a cardboard frame inside to hold the electronic bits. It’s “splash proof” and certainly cheap to make, but we’re a little worried about cooling and physical protection for the electronics inside, as they’re not exactly cheap and rugged components.

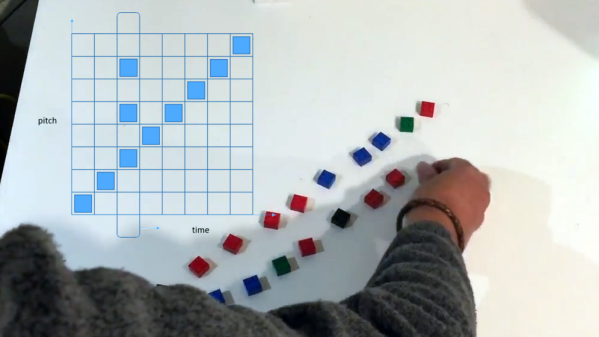

So what’s inside? An Nvidia Jetson TX2 board, a LiPo battery with some charging circuitry, and a standard webcam. The special sauce, however, is the software, which is available on GitHub. [Moovel lab]’s engineers have put together a nice-looking wifi-accessible mobile UI for marking the areas where you’d like the software to identify and tally objects. The actual object detection and identification tasks are performed by the speedy YOLO neural network, a task the Nvidia board’s GPU is of course well suited for.

As the Open Data Cam’s unblinking glass eye gazes upon our urban environments, it will log its observations in an ancient and mysterious language: CSV. It’s up to you, human, to interpret this information and use it for good.

A summary video and build time lapse are embedded after the break.

Continue reading “Open Data Cam Combines Camera, GPU, And Neural Network In An Artisanal DIY Cereal Box” →