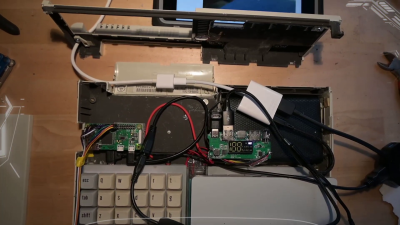

Need some kind of battery for a project? You can always find a few Lithium-Ion (LiIon) batteries around! They’re in our phones, laptops, and a myriad other battery-powered things of all forms – as hackers, we will find ourselves working with them more and more. Lithium-Ion batteries are unmatched when it comes to energy capacity, ease of charging, and all the shapes and sizes you can get one in.

There’s also misconceptions about these batteries – bad advice floating around, fearmongering videos of devices ablaze, as well as mundane lack of understanding. Today, I’d like to provide a general overview of how to treat your LiIon batteries properly, making sure they serve you well long-term.

What’s A Battery? A Malleable Pile Of Cells

Lithium-Ion batteries are our friends. Now, there can’t be a proper friendship if you two don’t understand each other. Lithium-Ion batteries are tailored for human needs by the factory that produced them. As for us hackers, we’ll want to learn some things.

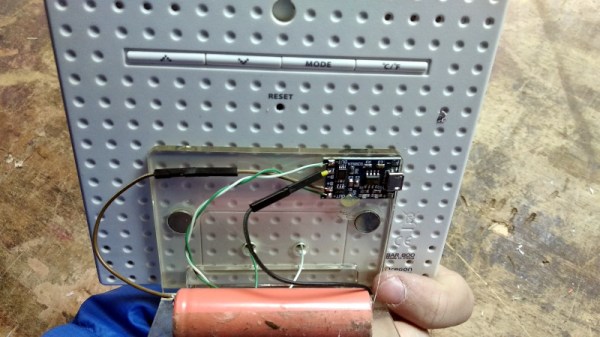

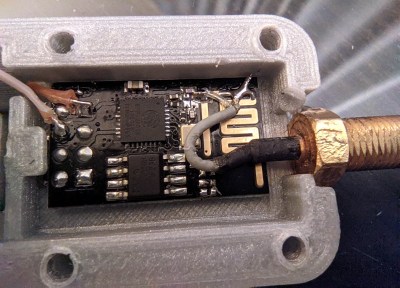

First thing to learn – a single LiIon “unit” is called a cell. An average laptop contains three or six Li-Ion cells, a phone will have one, a tablet will have from one to three. What we refer to as “battery” is typically one or multiple cells, together with protection circuitry, casing and a separate connector – most of the time all three of these, but not always. The typical voltage is 3.6 V or 3.7 V, with maximum voltage being 4.2 V – these are chemistry-defined, the same for most kinds of cells and almost always written on the cell. Continue reading “Lithium-Ion Batteries Are Your Friends”