Small wheeled robots are great for exploring robotics and it’s easier than ever to get started, thanks to growing availability and affordability of basic components. One such component is a small motorized wheel assembly commonly shown when searching for “robot wheel”: a small DC motor mounted in a gearbox to drive a single plastic wheel (inevitably yellow) on which a thin rubber tire has been mounted for traction. Many projects have employed these little motor + gearbox + wheel modules, such as these three entries for 2018 Hackaday Prize:

BoxBotics takes the idea of an affordable entry point and runs with it: build robot chassis for these wheels out of cardboard boxes. (Maybe even the exact box that shipped the yellow wheels.) Cardboard is cheap and easy to work with, making cardboard projects approachable to any creative mind. There will be an audience for something like a Nintendo Labo for robotics, and maybe BoxBotics will grow into that offering.

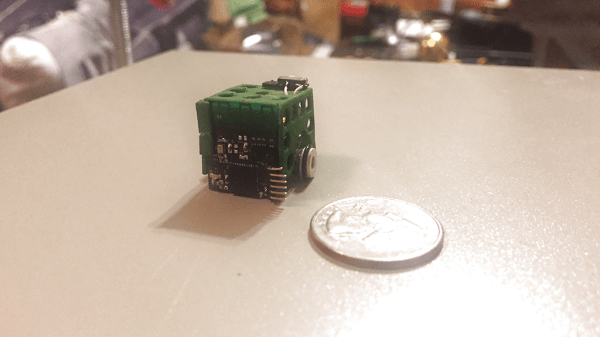

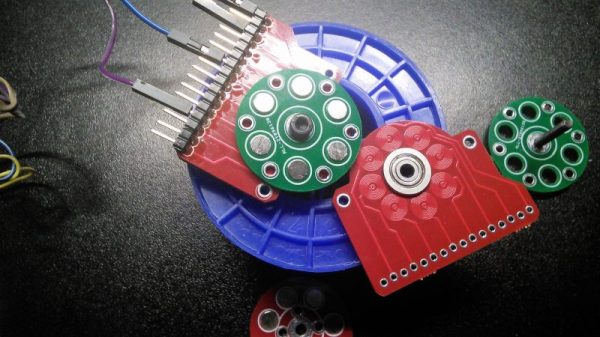

Cing also intends to make a friendly entry point for robotics and they offer a different chassis solution. Instead of cardboard, they use a circuit board. The yellow gearbox is mounted directly to the main circuit board making it into the physical spine, along with its copper traces serving as the spinal cord of the robot. While less amenable to mechanical creativity than BoxBotics, Cing’s swappable modules might be a better fit for those interested in exploring electronics.

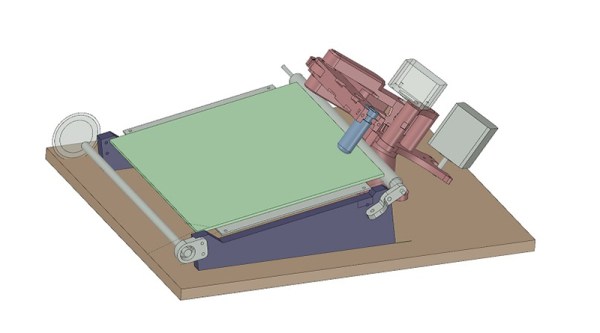

ROS Starter Robot caters to those who wish to go far beyond simple “make it move” level of robot intelligence. It aims to lower the barrier to enter the world of ROS (robot operating system) which has historically been the domain of very capable (but also very expensive) research-oriented robots. This project could become the bridge for aspiring roboticists who wish to grow beyond hobbyist level software but can’t justify the cost typical of research level hardware.

All three of these projects take the same simple motorized wheel and build very different ideas on top of them. This is exactly the diversity of ideas we want to motivate with the Hackaday Prize and we hope to see great progress on all prize contestants in the month ahead.