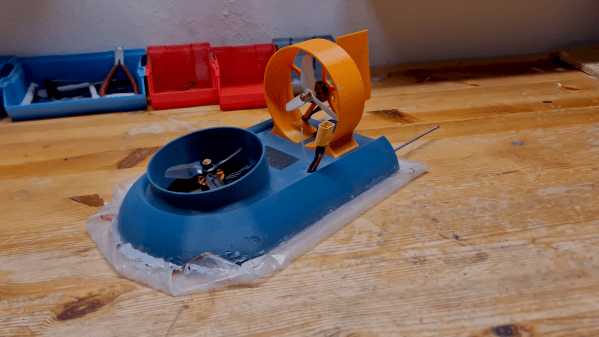

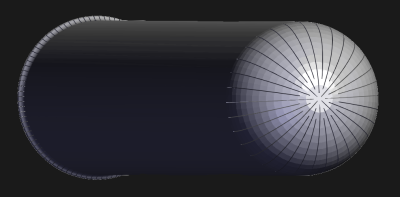

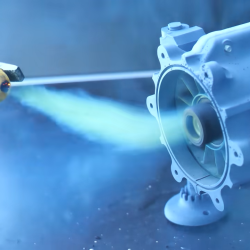

[Let’s Print] has been fascinated with creating a 3D printed axial compressor that can do meaningful work, and his latest iteration mixes FDM and SLA printed parts to successfully inflate (and pop) a latex glove, so that’s progress!

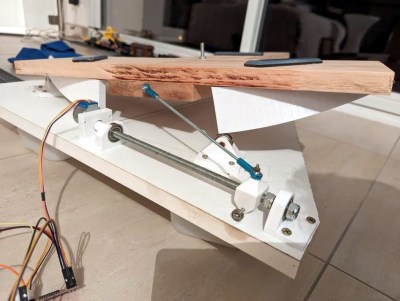

Originally, the unit couldn’t manage even that until he modified the number and type of fan blades on the compressor stages. There were other design challenges as well. For example, one regular issue was a coupling between the motor and the rest of the unit breaking repeatedly. At the speeds the compressor runs at, weak points tend to surface fairly quickly. That’s not stopping [Let’s Print], however. He plans to explore other compressor designs in his quest for an effective unit.

Originally, the unit couldn’t manage even that until he modified the number and type of fan blades on the compressor stages. There were other design challenges as well. For example, one regular issue was a coupling between the motor and the rest of the unit breaking repeatedly. At the speeds the compressor runs at, weak points tend to surface fairly quickly. That’s not stopping [Let’s Print], however. He plans to explore other compressor designs in his quest for an effective unit.

Attaching motor shafts to 3D printed devices can be tricky, and in the past we’ve seen a clever solution that is worth keeping in mind: half of a spider coupling (or jaw coupling) can be an economical and effective way to attach 3D printed things to a shaft.

While blowing up a regular party balloon is still asking too much of [Let’s Print]’s compressor as it stands, it certainly inflates (and pops) a latex glove like nobody’s business.

Continue reading “3D Printed Axial Compressor Is On A Mission To Inflate Balloons”