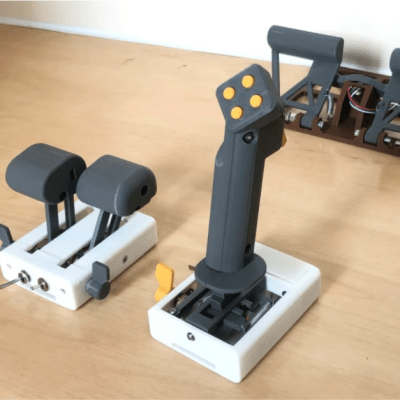

People making DIY controls to enhance flight simulators is a vibrant niche of engineering and hackery, and it sure looks like Microsoft Flight Simulator is doing its part to keep the scene lively. [Akaki Kuumeri]’s latest project turns an Xbox One gamepad into a throttle-and-stick combo that consists entirely of 3D printed parts that snap together without a screw in sight. Bummed out by sold-out joysticks, or just curious? The slick-looking HOTAS (hands on throttle and stick) assembly is only a 3D printer and an afternoon away. There’s even a provision to add elastic to increase spring tension if desired.

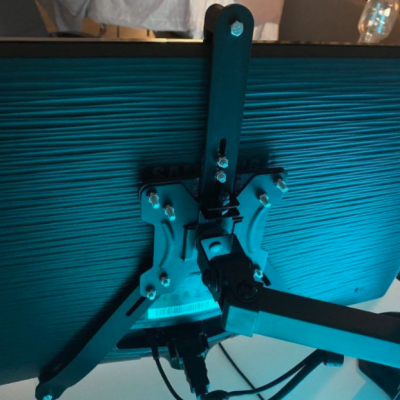

The design looks great, and the linkages in particular look very well thought-out. Ball and socket joints smoothly transfer motion from one joystick to the other, and [Akaki] says the linkages accurately transmit motion with very little slop.

There is a video to go with the design (YouTube link, embedded below) and it may seem like it’s wrapping up near the 9 minute mark, but do not stop watching because that’s when [Akaki] begins to go into hacker-salient details about of how he designed the device and what kinds of issues he ran into while doing so. For example, he says Fusion 360 doesn’t simulate ball and socket joints well, so he had to resort to printing a bunch of prototypes to iterate until he found the right ones. Also, the cradle that holds the Xbox controller was far more difficult to design than expected, because while Valve might provide accurate CAD models of their controllers, there was no such resource for the Xbox ones. You can watch the whole video, embedded below.

Continue reading “Xbox Controller Gets Snap On Joystick From Clever 3D-Printed Design”