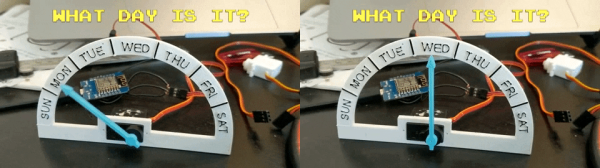

With much of the world staying at home at the moment, keeping track of our sanity and the day of the week is a bit of a challenge, especially without the normal daily routine to hold onto. To help with one of these problems, [phreakmonkey] has built a Day Clock. As the name suggests, it’s only purpose is to show what day of the week it is.

Avery simple device, the two main components are a servo and a Wemos D1 Mini, the popular ESP8266-based dev board. Using the NTPtimeESP library, it gets day of the week from the internet, and moves the servo to indicate the current day on a 3D printed face. Most readers should be able to whip one up in an hour or two, which can help keep sane in these interesting times.

For another Corona clock, check out [Elliot Williams]’ version that helps with keeping domestic peace. If you want to do something to combat the spread of the current epidemic, you can build a few face shields, make your idle computer available for Folding@Home or sew a few masks. Every bit helps.

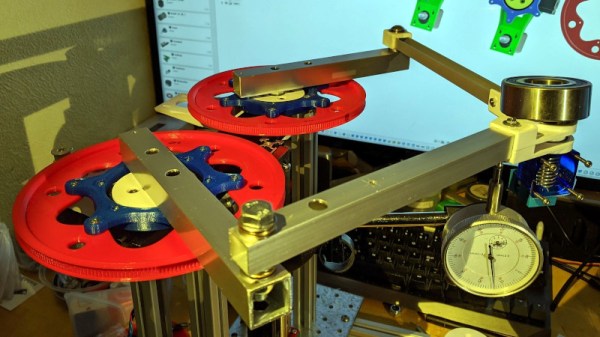

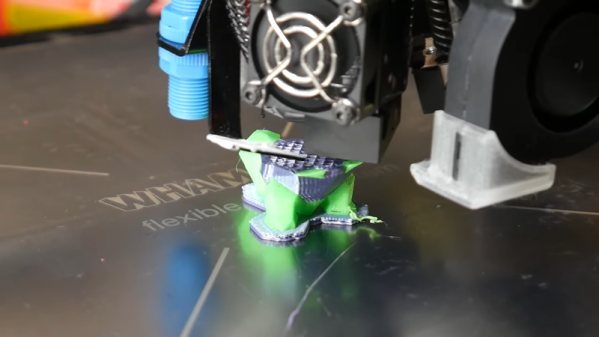

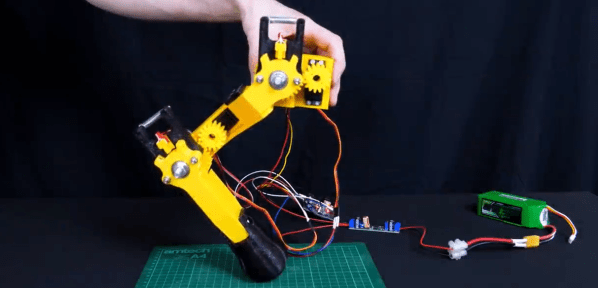

The 3D printed leg mechanism has two joints (hip and knee), with an RC servo to drive each. To make the joints compliant, both are spring-loaded to absorb external forces, and the deflection is sensed by a hall effect sensor with moving magnets on each side. Using the inputs from the hall effect sensor, the servo can follow the deflection and return to its original position smoothly after the force dissipates. This is a simple technique but it shows a lot of promise. See the video after the break.

The 3D printed leg mechanism has two joints (hip and knee), with an RC servo to drive each. To make the joints compliant, both are spring-loaded to absorb external forces, and the deflection is sensed by a hall effect sensor with moving magnets on each side. Using the inputs from the hall effect sensor, the servo can follow the deflection and return to its original position smoothly after the force dissipates. This is a simple technique but it shows a lot of promise. See the video after the break.