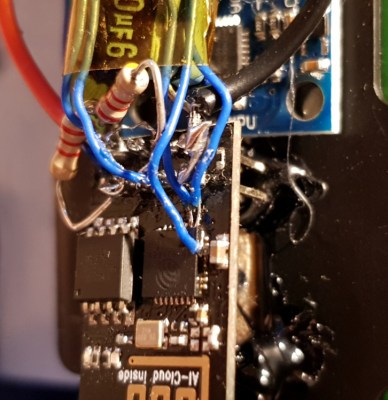

The ESP8266 has become such a staple of projects in our community since it burst onto the scene a few years ago. The combination of a super-fast processor and wireless networking all on the same chip and sold in retail quantities for relative pennies has been irresistible. So when [Petteri Aimonen] needed to make a wireless intercom system for cycling trips it seemed an obvious choice. Push its internal ADC to sample at a high enogh rate for audio, and stream the result over an ad-hoc wi-fi network.

The result was far from satisfactory, as while early results with a signal generator seemed good, in practice it was unusable. Significant amounts of noise were entering the pathway such that the resulting audio was unintelligible. It seems that running a wireless network causes abrupt and very short spikes of power supply current that play havoc with audio ADCs.

He’s submitted it to us as a Fail Of The Week and he’s right, it is a fail. But in a way that’s an unfair description, because we can see there is the germ of a seriously good idea in there. Perhaps with an external ADC, or maybe with some as-yet-to-be-determined filtering scheme, an ESP8266 walkie-talkie is one of those ideas that should be taken to its conclusion. We hope he perseveres.

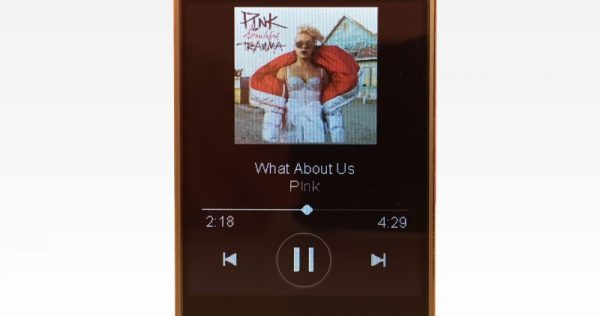

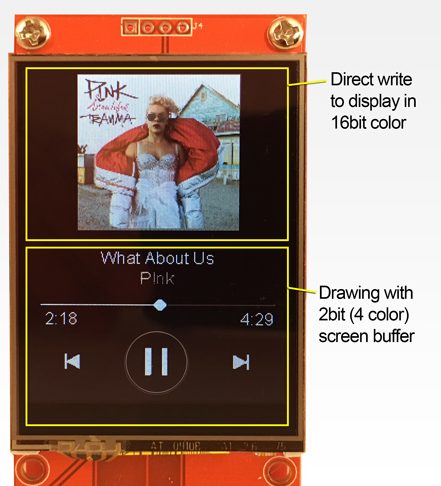

The second problem was smooth drawing. By the ESP’s standards the album art for a given track at full color depth is pretty storage-large, meaning slow transfers to the display and large memory requirements. [Dani] used a few tricks here. The first was to try 2 bit color depth which turned out atrociously (see image above). Eventually the solution became to decompress and draw the album art directly to the screen (instead of a frame buffer) only when the track changed, then redraw the transport controls quickly with 2 bit color. The final problem was that network transfers were also slow, requiring manual

The second problem was smooth drawing. By the ESP’s standards the album art for a given track at full color depth is pretty storage-large, meaning slow transfers to the display and large memory requirements. [Dani] used a few tricks here. The first was to try 2 bit color depth which turned out atrociously (see image above). Eventually the solution became to decompress and draw the album art directly to the screen (instead of a frame buffer) only when the track changed, then redraw the transport controls quickly with 2 bit color. The final problem was that network transfers were also slow, requiring manual