[NotLikeALeafOnTheWind] has created many LED-based display projects, and shares his method for making attractive LED panel frames and mounts. At first glance it may look as though slapping a rectangle of aluminum extrusion around a display is all it takes, there is also the mounting and management of wiring, power supply, and possibly a Raspberry Pi to deal with. The process of building an attractive frame also has a few hidden gotchas that can be avoided with a bit of careful planning.

Here is one tip that will resonate with some readers: don’t rely on specified dimensions of parts; measure the actual parts yourself. There can be small differences between what a data sheet says to expect, and the dimensions of the actual part in one’s hands. It may not be much, but it can be the difference between an ideal fit, and something that looks like a bit of a hack job.

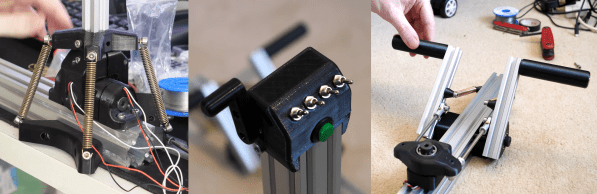

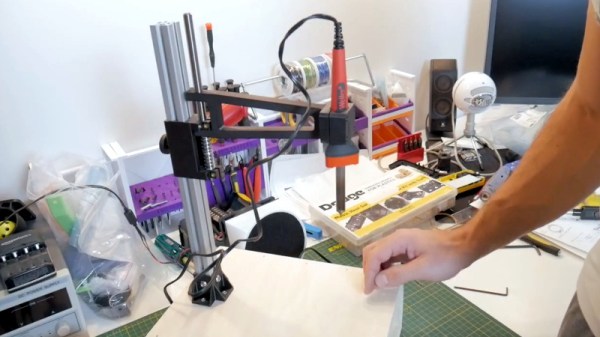

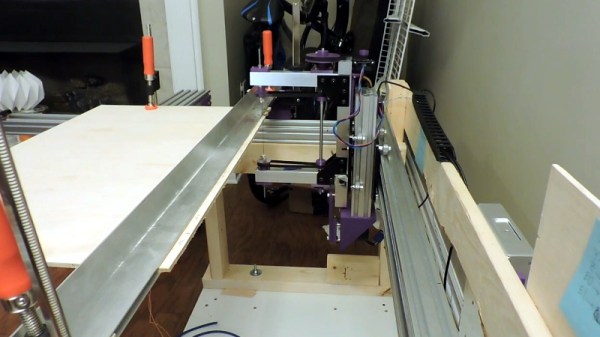

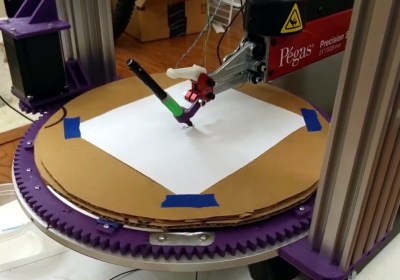

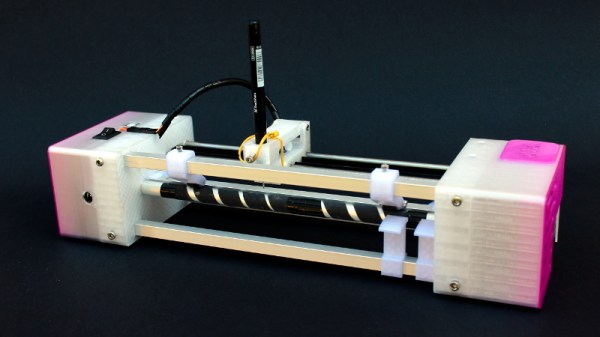

[NotLikeALeafOnTheWind] provides some basic frame layouts, and suggests using two- or three-channel extrusions to provide a flat bezel around the display edge if desired. Mounting the LED panel itself is done with magnetic feet and providing a length of steel bar to which the display can attach. This can provide a flush mount while avoiding the whole issue of screw-mounting the display panels themselves, or sliding them into channels. For mounting all the other hardware, a piece of DIN rail and some 3D-printed parts takes care of that.

The result looks slick and sturdy, and some of the tips are sure to be useful even if the whole process isn’t applied. We like the way the basic design scales and is flexible about the thickness and size of the LED panels themselves, making it a promising way to accommodate perfectly functional oddball panels that end up in the trash.