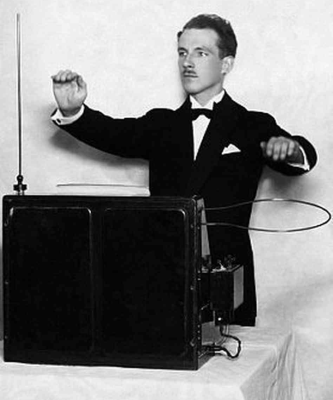

Many ham radio operators now live where installing an outdoor antenna is all but impossible. It seems that homeowner’s associations are on the lookout for the non-conformity of the dreaded ham radio antenna. [Peter] can sympathize, and has a solution based on lessons of spycraft from the cold war.

[Peter] points out that spies like the [Krogers] needed to report British Navy secrets like the plans for a nuclear boomer sub to Russia but didn’t want to attract the attention of their neighbors. In this case, the transmitter itself was so well-hidden that it took MI5 nine days to find the first of them. Clearly, then, there wasn’t a giant antenna on the roof. If there had been, the authorities could simply follow the feedline to find the radio. A concealed spy antenna might be just the ticket for a deed-restricted ham radio station.

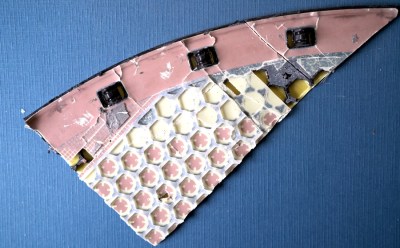

The antenna the [Kroger’s] used was a 22-meter wire in the attic of their home. Keep in mind, the old tube transmitters were less finicky about SWR and by adjusting the loading circuits, you could transmit into almost anything. Paradoxically, older houses work better with indoor antennas because they lack things like solar cell panels, radiant barriers, and metallic insulation.

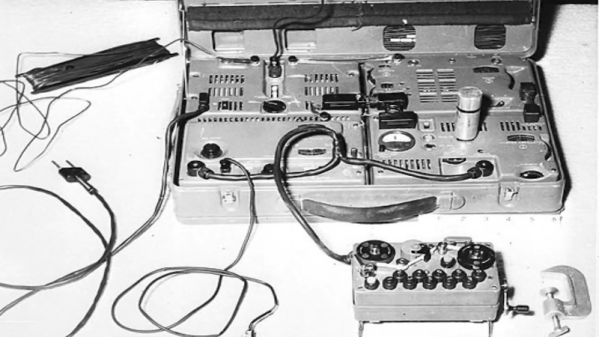

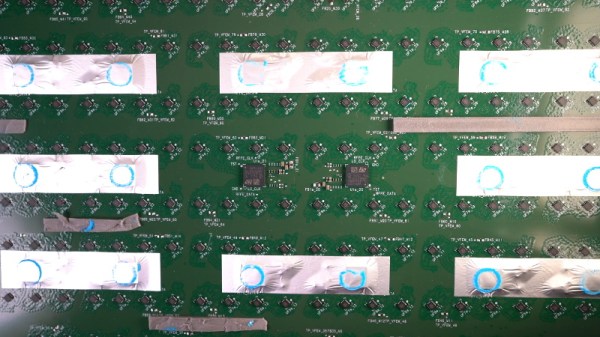

Like many people, [Peter] likes loop antennas for indoor use. He also shows other types of indoor antennas. They probably won’t do as much good as a proper outdoor antenna, but you can make quite a few contacts with some skill, some luck, and good propagation. [Peter] has some period spy radios, which are always interesting to see. By today’s standards, they aren’t especially small, but for their day they are positively tiny. Video after the break.