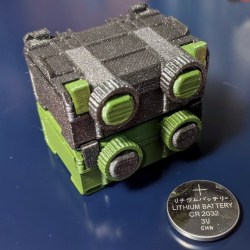

[Jacob Stanton]’s design for 3D-printable, stacking and locking boxes is a great example of design for manufacturability (DFM). MicroStacks show how part of good DFM is taking the manufacturing method’s strengths and weaknesses into account. [Jacob]’s boxes are created specifically with 3D printing in mind, which is great design whether somebody is making one, or dozens.

The boxes have sturdy parts that all print without any need for supports, fasteners, or post-processing. In addition, since no two 3D printers are quite alike and some print better than others, the parts are also designed to be quite forgiving of loose tolerances. Even on a printer that is less well-tuned than it could be, the design should still work. The boxes also have a nice stacking feature: a sturdy dovetail combined with a sliding tab means that once boxes are stacked, they’re not coming apart by accident unless something breaks in the process.

The boxes as designed are about big enough to store AA cells. Not the right size for you? One nice thing about a 3D-printable design that doesn’t need supports is that it’s trivial to uniformly scale the size of the models up or down to match one’s needs without introducing any print complications in the process. You can watch [Jacob] assemble and demonstrate his design in the video, embedded below.

Continue reading “To Lovers Of Small Boxes: A 3D Printable Design Just For You”