Bleach is a handy way to mark fabrics, and it turns out that combining bleach with a 3D-printed design is an awfully quick-working and effective way to stamp a design onto a shirt.

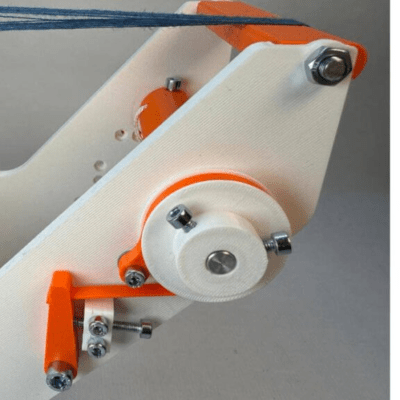

While conceptually simple, the details make the difference. Spraying bleach onto the stamp surface helps get even coverage, and having the stamp facing “up” and lowering the shirt onto the stamp helps prevent bleach from running where it shouldn’t. Prompt application of hot air with a heat gun (followed by neutralizing or flushing any remaining bleach by rinsing in plenty of cold water) helps keep the edges of the design clean and sharp.

We wondered if combining techniques with some of the tips on how to 3D print ink stamps would yield even better results. For instance, we notice the PLA stamp (used to make the design in the images here) produces sharp lines with a slightly “eroded” look overall. This is very much like the result of inking with a stamp printed in PLA. With a stamp printed in flex filament, inking gives much more even results, and we suspect the same might be true for bleach.

Of course, don’t forget that it’s possible to 3D print directly onto fabric if you want your designs to be a little more controlled (and possibly in multiple colors). Or, try silkscreening. Who knew there were so many options for putting designs onto shirts? If you try it out and learn anything, let us know by sending in a tip!

Continue reading “Make Custom Shirts With A 3D Print, Just Add Bleach”